Benelli is not the company we think of today for modern service pistols – and according to the sales record of the B76 family, they weren’t in the 1980s either. Designed in the early 1970s and put into production in 1976, the Benelli B76 is very pretty single-stack service pistol, notable for being an inertially locked design. Aside from the Sjogren shotguns of the very early 1900s, Benelli is really the only company to successfully market inertially locked guns – shotguns, specifically. They tried to do the same with the B76 pistols, but the result was basically a commercial flop. The whole family was:

– B76 – 9mm Parabellum, inertially locked, SA/DA trigger

– B76 Sport – same as B76 but with extended 5.5″ barrel, adjustable sights, and target grips

– B77 – .32 ACP, simple blowback, SA/DA trigger

– B80 – 7.65mm Parabellum, inertially locked, SA/DA trigger

– B80 Sport – same as B80 but with extended 5.5″ barrel, adjustable sights, and target grips

– B82 – 9x18mm Ultra, simple blowback, SA/DA trigger

– MP3S – 9mm Para or .32 S&W Long, 5.5″ barrel, extra fine finish, target grips, adjustable sights, and SA-only trigger

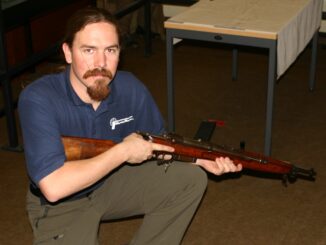

The B76 used a single stack 8-round magazine, had a relatively finicky disassembly process, and a not-particularly-ergonomic safety; all features which did not help it compete against the new generation of “wondernine” service pistols hitting the market at about the same time. Less than 10,000 were made by 1990, when the whole series was discontinued. Of those, less than 500 were the very high-end bullseye MP3S model – one of which we are thankful to have on loan from viewer Todd!

Strange mechanicals. I have never understood the 9×18 Ultra. On paper it seems to have identical energy to the 9×17 Kurtz and 9×18 Makarov. Is the original loading of 9mm Kurtz lighter than what we have today?

9×18 Ultra, aka 9×18 Police, is virtually identical to 9×18 Makarov, which is unsurprising as they each represent an effort to back down from an expensive short-recoil service pistol (Luger in 9×19 and Tokarev in 7.62×25) to a cheaper blowback design, with minimal loss in power. CIP lists are 1800bar (Ultra) vs. 1600bar (Mak), but considering the Mak has about 6% more bore ares, it’s equivalent to 1700bar on a standard 9mm (Luger/Ultra/Browning etc.) bore.

9×17/.380 ACP, on the other hand, was a much earlier cartridge, and not originally intended to compete with or approximate locked-breech cartridges like 9×19, but rather designed as an upgrade to 7.65/.32 ACP pocket pistols. To keep things safe and reliable with minimal redesign of these pistols, its pressure was kept quite low (CIP Pmax: 1350bar), and its ballistics are correspondingly weak — typically 10-20% less energy than the later 9×18 cartridges.

While modern powders do allow specialty 9×17 ammo to be loaded for higher energy than the historical standard without exceeding this pressure limit, of course the same technical advances can be applied to Makarov/Ultra to keep them ahead by the same 10-20%.

To understand why we have three such similar cartridges, it’s important to note the history — the key thing is that Ultra came around twice, first in the ’30s as a pistol for the Luftwaffe (but they didn’t order it, and so the whole thing disappeared); second, when it was revived in the ’70s (and barely anyone ordered it, so this time it only “almost” disappeared).

At each step, introducing the new cartridge made sense:

* 9×17 (USA, 1908): no suitable cartridge existed

* Ultra (Germany, 1936): 9×17 was a little too weak, and no other existed

* Makarov (Russia, 1951): 9×17 was a little too weak, Ultra had already disappeared

* Ultra again (Germany, 1972): 9×17 was a little too weak, Makarov was behind the iron curtain

Today, with 9×18 Makarov weapons and ammo being readily available world-wide, it seems incredibly redundant to have both 9×18 cartridges, but during the Cold War it did make some sort of sense.

It is worth adding that few years before 9×17 cartridge 9×20 mm SR cartridge:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/9mm_Browning_Long

was introduced in Europe by FN together with Browning No.2 automatic pistol (blow-back operated)

https://modernfirearms.net/en/handguns/handguns-en/belgium-semi-automatic-pistols/fn-browning-m1903-eng/

which despite being improvement over No.1 automatic pistol [7,65 mm Browning / .32 Auto cartridge] proved less successful in terms of examples sold with slight less than 60 000 [made by FN] as opposed to more than 700 000 in case of older design (Husqvarna of Sweden also produced this automatic pistol after license was bought and made 94000, but even combined with FN production this is less than production of No.1).

Excellent point. I should have remembered that one, it’s very much a peer of 9×18 Ultra and 9×18 Makarov in ballistic terms.

9mm Browning Long, 9mm Glisenti, 9mm Ultra, 9mm Makarov… energy wise all are in the same ballpark, that of the “most powerful 9mm cartridge that can be fired by a blowback pistol without weight disadvantages”.

The same guy that designed the 9mm Browning long, designed the .380 ACP as the most powerful round for pocket handguns, and the .38 ACP as the ideal 9mm round for breechlock pistols (and infact the .38 ACP is in the same ballpark of the 9mm Parabellum, 9mm Largo and several others).

“9×18 Makarov”

Origins of these cartridge are quite vague.

After WWII loot German automatic pistols were examined by Soviet experts.

Most probably first intention was to develop new automatic pistol chambered for 7,65 mm Browning [.32 Auto] cartridge, soon later to use 9×17 Kurz [.380 Auto] to finally settle on own 9×18, which in fact is bit bigger than other 9 mm and it would be more precise to call it 9,2×18. There were many automatic pistol designs submitted, in three calibers, see photos: https://www.kalashnikov.ru/k-yubileyu-sozdaniya-pistoleta-makarova/

[I hope German influence is clear even if you do not understand text]

to finally lead to what we known as Makarov. One of possible reason to use 9,2 rather than 9 bullet, was that such solution allowed firing 9×19 Parabellum cartridge in 9×18 Makarov chambered, but not vice versa (while 9×19 Parabellum might have heavier powder charge, “loose” fit of bullet-rifling, prevents excessive pressure build-up, thus 9×19 Parabellum might be fired, with accuracy heavily hindered but generally safely from Makarov automatic pistol).

I was under the impression that this was a lever-delay system. Did I mess up and get the wrong pistol family?

Yeah, watch the video. Ian explains why this is not a lever-delayed system, and is instead an internal-delayed system.

An easy test exists. Ian could clamp his (pawn shop) gun into a vise, then fire it. An inertia operated gun in this case would not cycle. I’m confident enough to predict that this one will.

Wonderful! I knew vaguely of the Benelli pistols, but I had no idea they used inertia locking operation.

I just watched your shooting vid on youtube (dropped a day early?), and I think I know why the MP3S was malfunctioning at first. I believe it is due to the peculiarities of inertia locked operation. The heavier weight of the MP3S combined with the two handed grip, didn’t allow enough recoil movement. When you switched to single hand shooting, then the gun could recoil enough for the mechanism to function.

The problem was the opposite of limp-wristing with a conventional recoil operated pistol. (If I understand the inertia operation principle correctly) The Benelli should work better when limp-wristing.

Holy cow! Never thought I’d say this, but it’s very obvious that Ian is wrong.

The muliplication he’s seeking happens because the locking shoulder is cut at a significant angle, just like the locking shoulder on Glock 25, or the locking surfaces on CMMG Raially-Delayed guns. Therefore, the bolt exerts a significant force upwards. The flapper converts that force into the rearward motion of the slide, adding a mechanical disadvantage, characteristic of delayed blowback guns (except the stupid Thompson AutoRifle).

One other thing. In order to give the necessary energy to the operating system, there must also be a motion together with the force (distance traveled multiplied by force is the energy). The bolt motion upward is the motion part that transfers the energy to the slide in this case.

If someone wants to see how an inertia system works, there was an excellent video recently by Ian himself on the subject of NeoPup, which provides a great example. A less great example is Ian’s old video about a German WWI auto-loader. That system was garbage, although inertia-operated also.

The above is not matched by the text in the patent, BTW, which says ” Once the inertial force of said bolt carrier has failed, the residual pressure of exhaust gases applies a force to said bolt which causes the bolt to rotate (…)”.

A masterpiece in pistol design. US patent Nr.3893369.

A true locked breech design. Breechbolt locking surfaces separates from the receiver with same lenght from the pivot point,from beginning to end and not with an increased value as occured in the delayed blowback samples. Besides, lever delay needs a receiver pivot point to effectively acceralate the bolt carrier. Chamber grooves should be provided to match the velocity with the lesser mass with higher speed of extracting empty case with higher mass with acceralating slide.

Very similar operating approach formerly was used in Reising SMG. lMHO.

It’s another Blish principle of modern times.

That’s a very cool pawn shop find!

I hope that the pitting isn’t deep. It doesn’t look deep.

I thought Benellis were so cool in the 80s. Unfortunately I listened to friends who said that the only 9mm P pistols that had any resale value were red 9 broomhandles lugers and Hi Powers.

So I went against both the. And myself and bought a Lahti then a Walther P38.

All of the game keepers around here have 8 shot Benelli 12 guage autos. Unfortunately the pistols might not have been a commercial success for them, but their shotguns seem to have made up for that.

Ok, operating mechanics;

My take on what’s happening (it’s a long time since I read the patents).

On firing, the case head pushes the bolt backwards

The rear of the bolt tries to rise up the angled (not a locking) surface

That rising up is resistered by the inertia of the slide

The bolt has to accelerate the slide, before the rear of the bolt can rise up and escape from the angled surface.

The little flanged knob, carries the bolt and stops it from dropping out of the slide.

What would I categorise the operating system as?

Delayed blowback

Sorry Ian.

I think you’re onto something. Watching the video he shows a fluted chamber which means it is likely a blowback of some kind. My take on it is that it’s a retarded blowback not a delayed one, using George Chin’s definitions. It looks like the system is locked upon firing but the recoil of the gun allows the slide to go back enough to unlock the system using the knob on the bolt and slot on the slide, and enough residual pressure exists to blow the slide and bolt back once it’s all unlocked.

Actually, the little flanged knob, keeps the back of the bolt up until the front of the bolt jams the cartridge case against its headspace stop.

Then the flanged knob is forced to the end of its T slot, and the rear of the bolt can be forced down into the locked position.

This is a tricky one to categorize, because the same mechanism could be either inertial-unlocking or delayed-blowback depending on the exact angle of the locking shoulder, or even just on the coefficients of friction between the various moving parts. The patent claims inertial unlocking, but that doesn’t prove much — it wouldn’t be the first time an inventor misunderstood how his invention actually works, nor the first time a mechanism was modified between patent and production.

To me, the angle looks like it should certainly act as a delayed-blowback if well lubricated. On the other hand, while I haven’t seen the shooting video, Brad’s observation suggests that in the real world, it’s at least partially dependent on inertial unlocking — if the angle and friction were such that it did operate by pure delayed-blowback, the rigidity of grip shouldn’t make a significant difference between one-handed and two-handed shooting.

Either way, it means outsider in area production automatic pistol design.

Delayed blowback is my take too; I do not see much of inertia function in it. As you state correctly, the lock surface angle is critical. Once the breech piece raises, whole slide group is ready to move.

Benelli guys are tinkerers, no doubt smart people.

Hmmmm

There could have been something that was lost in translation.

Blowback and delayed blowback do both rely on inertia

Regarding to operating system; it looks to work as delayed blowback as a tilting block locked breech. lMHO.

Remember “Dolls Head” lock on old British doubles?… lts working recess are angled and seems not functions as a lock, but it works so in assosiation with sliding locking bolt… ln this sample the slide with inertia works like the sliding bolt of a double shotgun and applies pressure through the mini lever over the breechbolt gaining a forward thrust by recoil as using moving tolerances like a clamp until the recoil pulse ends. lf the rear seat of breecbolt were not angled, the same should need a forward movement as pressing the barrel at same direction to get out of the locked position throuh a rotating movement centred on top front side of the locked bolt. lMHO.

Also, remember any sample of delaying operation with a moving support leverage point?… How effective could it be… Advantage should be on the bigger mass…

I have a Benelli B76 and agree with Keith’s description of how it works. When the back of the bolt cams up the angled surface it lifts the front of the flapper. Because the rear of the flapper is contained by the top of the slide it pushes backwards when its front is lifted, accelerating the slide.

After the slide has started its rearward movement the flanged knob pulls the bolt along. If the bolt isn’t mechanically attached to the slide, the cartridges in the magazine pushing up on the bolt could prevent it from moving backwards enough for the next cartridge to rise up in front of the bolt face.

What Ian didn’t mention was that the recoil spring includes compression washers to buffer the frame at the end of the slide’s rearward travel. I believe this is necessary because the slide has been accelerated and therefore has to be decelerated more than in locked breech designs to prevent frame damage. (the H&K P9S that also accelerates the slide, but with a roller delay system, has a polyurethane buffer for the same reason).

While I haven’t done what Pete suggests and fired my pistol clamped in a vice, I have held the pistol stationary, pushed a dowel down the barrel and it easily unlocks.

The early Ruger LC9 I have has the same type of vertically-sliding safety switch. Not very bueno, but with the long double action trigger pull, it’s not needed.

I thought .32 S&W Long was a rimmed revolver cartridge. How well would it work in an automatic?

“.32 S&W Long was a rimmed revolver cartridge”

True.

“How well would it work in an automatic?”

Generally, enough well in target automatic pistol, to be used in competition. Like for example GSP https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walther_GSP

There were attempts to use existing revolver cartridges in dawn of automatic pistols era, like for example UNION automatic pistol: https://guns.fandom.com/wiki/Reifgraber_pistol

but generally no viable service automatic pistol for rimmed revolver cartridge appeared at this time. Automatic pistol for rimmed revolver cartridge would also appear later, like for example COONAN: http://www.coonaninc.com/product/357-magnum-classic/

but it production would virtually all the time remain at “meh”-level compared to automatic pistol using rimless or semi-rimmed cartridges.

I suppose nobody is surprised that .22 LR self-loading guns work, right? How about the SVT? The Bren? The Coonan .357?

I realize that I’m joining the party rather late, but just as a data point, the Benelli B76 manual has a section that is entitled:

“Operating description of the delayed blow-back Locking System”

To muddy the 9×18 Ultra waters further, I can confirm that the B82 is actually not a direct blowback. I currently own a B82 and I have previously owned a B76, and the internal mechanism is identical.