In the aftermath of World War Two, the Austrian Army was basically disarmed and disbanded. When it was allowed to reform in the 1950s, it needed new armaments, and in 1958 it adopted the SSG-98k as a new sniper’s rifle. This replaced the leftover German K98k snipers that had been used by the small post-war Austrian police and border guard forces.

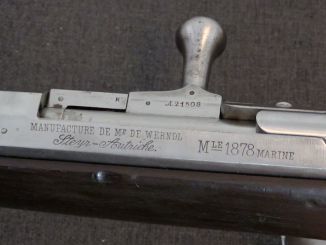

Essentially, the SSG-98k was a surplus German Kar 98k Mauser with a new 7.62x51mm barrel (Austria was not a NATO member, but used the NATO cartridge), a cut-down stock, commercial Pachmayr recoil pad, and a Kahles 4x31mm ZF-58 scopes. A variety of base rifles were used for these, from very early pre-war German Mausers through post-war French-occupation Mausers.

The SSG-98k served for about ten years, being replaced in 1969 by the much more advanced Steyr SSG-69. Some remained in inventory into the 1980s.

I have a set of those 6×30 binoculars which my father got from a German officer who surrendered to him in the Rhur pocket in the spring of 1945. They’re rather good optics.

The mentioned HBA ink stamp in the scope cover stands for the Heeresbekleidungsanstalt, the Armed Forces Clothing Agency.

Did the Austrians conduct accuracy tests to determine which rifles to modify

Testing would have been pretty pointless given that the barrels were being replaced.

I hope Ian gets to the MG74 while he looks at Austrian weapons…

So essentially, as Ian said, they were the equivalent of “sporterized” standard Kar98K rifles except for being rebarreled to 7.62 x 51mm.

Which brings us to the question, just how “super-accurate” does a “sniper rifle” need to be?

During WW2, pretty much every combatant just bolted ‘scopes onto standard infantry rifles and called them “sniper rifles”. In reality, and contrary to myth, few were actually tested and selected for better than average accuracy first.

As I’ve previously stated, generally any rifle with the telescopic sight offset to the left to allow clearance for either stripper-clip loading (or in the case of the M1 Garand, en bloc clip ejection) would be largely useless beyond about 400 meters due to the parallax problem cause by that scope offset.

That being said, and again contrary to myth, most “sniper” kills were at only slightly greater ranges than regular infantry rifle kills; about 200 to 250 meters as opposed to 100 meters or less. Because in most cases, that would be about as far as the sniper and/or spotter would be able to actually see a potential target.

In the case of the legendary (now known to probably be very legendary, i.e. mostly made-up) Stalingrad exploits of Zaitsev & Assoc., most kills were at 100 meters or less- often a lot less, as in “medium pistol range”.

Once the range gets beyond 300 meters, it’s mostly a job for the GPMG, mortar, or whoever has the radio to call in artillery or CAS.

Seen in the light of that reality, these rifles were probably good enough for all practical purposes, and in fact better-designed and built than the average.

Most military “snipers” would probably be just as well served by a good-quality commercial sporting rifle in an adequate caliber (like .270 Winchester or even .243 Winchester) with a properly-installed sporting fixed-magnification four to six power telescopic sight on top (as in directly over the bore and properly boresighted at installation) as they would by a semi-custom “super sniper rifle” with all the “modern must-have” bells and whistles costing upward of $10K apiece.

At under 300 meters, the target is unlikely to notice the difference as regards to what just killed it.

clear ether

eon

Reference Source about the Garand?

I think a distinction needs to be made between actual snipers and what are actually more “designated marksmen”. The dedicated sniper is a guy who goes out and stalks specific enemy targets while also conducting reconnaissance for his unit. The guy with the accurized rifle in every squad? They ain’t snipers, because they’re not as well-trained, nor are they operating alone as a part of a dedicated sniper team effort.

In the US Army, there’s usually a bit of an issue with the actual assigned snipers. They’re typically not in the line units; they’re a part of the headquarters element, usually working for the battalion XO and/or the S2 intel officer. They’re not with the line units; they’re out doing their own thing, reporting back to HQ, and tasked by HQ directly. An awful lot of the time, the usual run of battalion commanders and their executive officers have not clue one about how to properly use their snipers, but when you do find someone who does? Hooo-boy, do you get some interesting results if the snipers are any good.

I did the Observer/Controller thing down at the Joint Readiness Training Center there in Louisiana at Fort Polk. The rotation before the one I O/C’d on had had a commander who’d cut his teeth as an enlisted sniper back in the 1980s, and he knew his stuff when it came to using them. He also had a stellar set of snipers, and they proceeded to wreak havoc on the OPFOR down there, not least because the guy actually running the snipers in that unit had actually been assigned to the OPFOR unit at Polk before his assignment as the sniper leader. He knew the ground, he knew the enemy, and between all that, they managed to rack up an obscene number of kills on the OPFOR. When that unit later went to Iraq, initially under the same commander, they did a bunch of amazing things with their snipers.

I think Austrian doctrine has more of a Designated Marksman flavor than that of the usual conception of “sniper”, where the sniper teams are out operating on their own. I could be mistaken, but…

It all goes back to “what is the mission”?

Is the “sniper team” primarily out there to kill “high-value” enemy personnel? To harass enemy units with targeted killing of anybody fool enough to stick his head out? Or are they there to observe enemy activity and report that back to HQ?

Three distinctly different and not necessarily complementary SOPs.

Marines call them “Scout/Snipers”, indicating that the “scouting” part is the more critical role. During The Great Patriotic War, Russian Army snipers’ credo was “While remaining unseen, I observe and destroy“.

Major Robert Rogers’ (possibly apocryphal) rules had one on that;

I’ve always been leery of an officer following a “game plan” in exercises. Often, those seem to be designed less to teach and practice effective war-fighting and etc. skills than to confirm the theories of somebody up the line sitting in an office.

A friend of mine saw it repeatedly in ROK along the DMZ back in the Eighties, the one place you’d think everybody would be more interested in The Real Thing than what got pats on the head from somebody in the Pentagon. “You confirmed my theory! Good Boy! You’ll get mentioned in my next presentation to the JCS!” (As.If.)

E.E. “Doc” Smith nailed it in Second Stage Lensman, when Kinnison, masquerading as Traska Gannel, “won” a wargame by essentially ignoring every order he’d been given;

The temptation in “wargaming” to do what gets good scores is strong. it becomes a personality thing, not unlike sucking up to a superior for promotion. In fact, it’s often part of that.

“Sniping” may be an area in which we have to decide what it’s all about first. Based on what has or hasn’t worked effectively previously.

Submitted for your approval. 😉

cheers

eon

One of the big issues you run into with a peacetime army environment is that because there’s no active enemy around to inject a note of reality into things, you wind up with a bunch of conformists running everything at all levels. And, they tend to default to the doctrinaire “what worked last time” mentality, because that’s how the military works. Innovation isn’t something the military does, unless it’s just lost a major war, or there’s a hell of a lot of external pressure demanding it. And, there are reasons for that; innovation is risk, and risk gets people killed. It ain’t exactly accidental that the military is the most “resistant to change” component of any society.

This is what drives a lot of the things you highlight here. It’s the equivalent of the idea businesses used to have that was expressed as “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM…” If it worked before, you won’t be criticized until that thing which worked has been utterly discredited by some real-world defeat.

It’s just the way things are, in any military.

I have never really bought into the idea that it’s a good idea to train people to a fixed standard based on fixed, inflexible doctrine. You can’t do the set-piece thing and expect good results when those units get to combat. That’s mostly what’s gone wrong for the Russians; all their training is scripted. The problem with that is that you have to get your scripts “just right” if you want to win. Wrong script=defeat. A lot of the problems for the Russians have come because they’re counting on their opponents following the script, which they’re under no obligation to do. Russian mindset was that them merely putting troops into Ukraine would result in the collapse of Ukrainian resistance, automatically. This obviously didn’t work out that way, because the Ukrainians embraced the benefits of chaos and then every single Ukrainian in their path refused to cooperate with their script, which completely borked Russian plans.

The root problem is that a lot of the people who gravitate towards the military in any culture tend to be the sort of people who are more comfortable in a fixed, unchanging, regimented reality. Which they then often tend to re-create in their own minds, resulting in what can only be described as an overall delusional worldview if the actual conditions have changed out in the real world. Which is how you get the various cavalry elements from all sides sitting around and waiting for the war to start conforming to their mindsets and worldviews in WWI–The majority of them simply couldn’t conceive of fighting a war in any other way. You see that same thing in a lot of modern military forces; I had a hard damn time trying to even discuss the need for training the various “slice elements” from all the support arms at the National Training Center. The people running the system could not even conceive of a need to train those units, but I’m sitting there having served a considerable chunk of my career at that point serving in corps-level Combat Engineer units that never got the chance to train at the NTC, and yet were supposed to be split up and sent out to support divisional units in combat. If you were looking at it from my perspective, what happened to the 507th Maintenance Company in Iraq was exactly what I was projecting would happen back in the late 1990s. Every unit forward of the line of departure has to have the training and experience to operate in a divisional operational/tactical environment. Yet, the guys running everything were locked into this mentality where “only divisional units fight”.

I’m actually surprised that there weren’t more incidents like the 507th. There were a lot of units that were equally unprepared for war, because the commanders couldn’t conceive that they’d ever need to.

It’s a failure to imagine, a crisis of “what if”, and most military structures encourage this because of their inherent nature. You have to break the damn mentality, and that’s really, really hard.

I think that the best thing to do is to actively ensure that everything from basic training on up is built and structured to emphasize the inherent chaos of war, and to encourage people to approach everything with a learning mentality. You should never walk into a situation and say “I know what to do” without stepping back and observing whether or not that “what to do” is actually working. You have to set things up such that people go into everything with a sense of insecurity about everything they’re doing, because they need the mindset that they have to observe reality and then adapt to it.

This is probably the one thing about Colonel Boyd’s theories that a lot of people miss; they don’t get that the OODA loop exists at every level, at all times. You have to observe everything in the combat environment, and then have the honesty with yourself to acknowledge the reality of what you’re observing, then orient yourself to cope with that reality, decide what acts are necessary, and then actually act effectively. This is super hard to do at the operational and tactical level in peacetime, because you’re providing all your own opposition, who’re going to be your guys, and who’re going to be working off your own scripts.

Drug dealers often say “don’t get high off your own supply”. This is a truth that also applies to doctrine and training; you have to have the reality of things imbued into your military microcosm, because what you’ve preconceived of as “likely enemy actions” ain’t actually all that likely, when you get down to it. You don’t know what they’re going to do until you’re well deep into operations against them, and even then… You can’t count on them not doing their own learning under fire.

“(…)Which brings us to the question, just how “super-accurate” does a “sniper rifle” need to be?(…)”

Observe that presented weapon was adopted in same year as Sturmgewehr 58, see 9th image from top http://modernfirearms.net/en/assault-rifles/belgium-assault-rifles/fn-fal-l1a1-c1-slr-eng/ which has accuracy very far from sniper.

I am interested to read that the French troops stationed in Austria until 1955 were equipped with Kar 98k’s. Did France not have enough of their own rifles, or were they being exceptionally frugal?

Keep in mind that when France fell in June 1940, production of a lot of their domestic military arms simply stopped. The Germans weren’t interested, as most of them fired French “proprietary” rounds not interchangeable with Wehrmacht standard (unlike Czech or Polish arms, for instance).

While Free French units were armed with a conglomeration of American and British small arms (FF units on D-Day often had British 0.303in Brens combined with American 0.30in M1903A3 rifles), French Forces of the Interior (FFI) units quickly rearmed with German weapons, because 7.9 x 57mm and 9 x 19mm ammunition was more easily obtained than 7.5 x 54 or 7.65 x 20. Often, factories and storehouses used by the Wehrmacht were ready sources of both arms and ammunition. Waste not, want not.

After the Liberation, the French Army continued using German weapons that were in many cases being built in French and other countries’ factories during the Occupation.

Among other things, the Foreign Legion’s standard weapons were almost all German until the mid-1960s, notable the Kar98k, MG34 and MG42 in 7.9 x 57mm, and the MP40 and P.38 in 9 x 19mm.

The P.38 was a substitute standard pistol for the French Army right alongside the standard MAS 1950 until the adoption of the Beretta M92 in 1987. Considering that production of the P.38 continued at Manhurin for commercial sale until that time, this was a sensible procedure.

So French units in Austria using Austrian-made Kar98s in 7.9 x 57mm would just be another example of French Army practicality. As the old American saying goes, you “dance with the one what brung you”.

cheers

eon

Eon:

Very good points. The French started production of the MAS36 again after the war ended, but in the period to 1960 were fighting in Indochina and Algeria. It may well have been easier to use Mausers et al in Austria, which was really a garrison operation, and send new production to the areas of conflict.

As to the P38, yes it was made in France, along with the PP and PPK. I would rather have had a P38 than a MAS50, as I find the French safety catches rather cumbersome.

I am surprised at you saying the Foreign Legion used so many German arms until the 1960s. Obviously, a lot of the Legionnaires would have been very familiar with German weapons :). Most newsreel I have seen from Algeria shows the French forces using French weapons, mainly MAS36 rifles and MAT49 SMGs. I have seen quite a few MG34s, but not MG42s. One thing that did strike me seeing newsreel from the time was that a large number of M1 carbines and Thompson SMGs seem to have been used, they crop up a lot. Also a fair few BARs. As you say, the French had to make do with what they had. Thanks for your comments.