The Breda Model 30 was the standard Italian light machine gun of World War II, and is a serious contender for “worst machine gun ever”. Yes, given the choice we would prefer to have a Chauchat (which really wasn’t as bad as people today generally think).

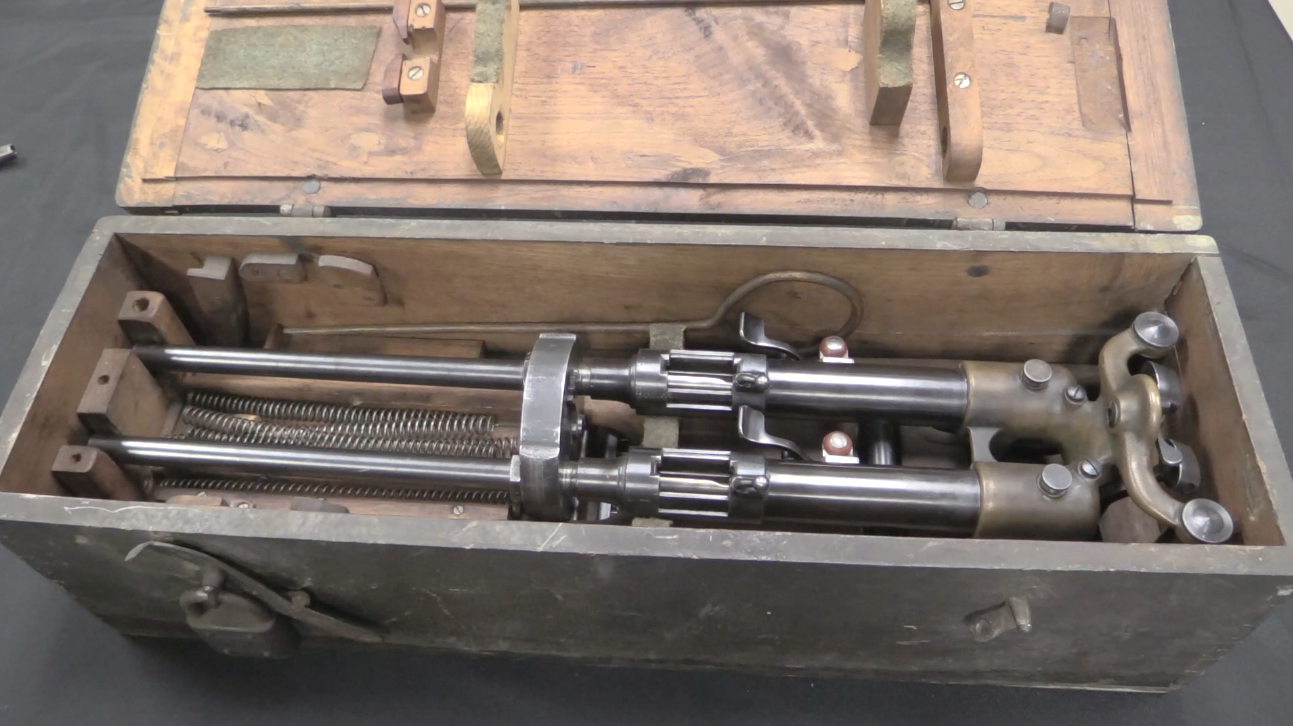

The Breda 30 suffered from all manner of problems. To begin with, it was far more complicated than necessary. The amount of machining needed to build one is mind boggling compared to contemporary guns like the ZB26/Bren or BAR. And for all that work, it just didn’t work well in combat conditions.

Mechanically, the Breda used a recoil-delayed blowback mechanism, managing to get all the possible downsides of both. The recoil action meant that the barrel moved with each shot, so the sights were mounted on the receiver to keep them fixed. This seems like a good idea, but it meant that the sights would need to be re-zeroed each time the barrel was changed. To compound this, the gun fired from a closed bolt which made it more susceptible to overheating and it was recommended to change barrels every 200 rounds or so. The action also lacked any primary extraction to help break the empty cartridge cases out of the chamber. Instead, an oiling mechanism was built in to lightly oil each cartridge on feeding. This allowed the gun to extract without ripping rims off the cases, but was a disaster waiting to happen on the battlefield. In places like North Africa, the oil acted as a magnet for sand and dust, leading to quick jamming if the gun were not kept scrupulously clean.

The next huge judgment error on Breda’s part was the magazine. The thought behind it was that magazine feed lips are easily damaged in the field, and they can be protected by building them into the gun receiver rather than in each cheap disposable box magazine (the Johnson LMG and Madsen LMG recognized this issue as well). However, Breda’s solution was to make the 20-round magazine a permanent part of the gun. The magazine was attached to the receiver by a hinge pin, and was reloaded by special 20-round stripper clips. This meant that reloading took significantly longer than changing magazines, and any damage to the one attached magazine would render the gun inoperable. As if anything else were needed, the magazine was made with a big opening on top to allow the gunner to see how many rounds remained – and to let more of that North African sand into the action.

Most of the Breda Model 30s were made in 6.5 Carcano, but a small number were made in 7.35 Carcano when that cartridge was adopted. The rate of fire was about 500 rounds per minute, which was a bit slower than most other machine guns of the day.

We haven’t had a chance to take one of these to the range ourselves, but there is a decent clip of one being fired and reloaded on YouTube:

We also have some photos showing some details of the Breda 30 (thanks, Joe!) and a manual on the gun compiled by British troops in Africa in 1941.

[nggallery id=161]

I’ve got a picture somewhere of Italians using these during the Russian Campaign, in the winter. Subzero temperatures, and an oiling mechanism. I can’t imagine that the results were any better…

Did you ever encounter a firing table for the 7.35 mm cartridge?

Ethiopia, Albania, Cyrenaika: total failure. Even the desperate-for-guns Nazi Germans didn’t want them.

IIRC the japanese MGs had oilers as well, and it was common practice with the Walther OSP (the little sister to the GSP in .22 short) for Olympic Rapid Fire before the rules changed.

Some of the Japanese guns used oiled cartridges (Type 11, 92, and 96 IIRC), but not the mainstay Nambu Type 99.

Type 99 (as well as its predecessor, Type 96 LMG) had an oiler built into magazine loader.

Probably the first MG to have built-in oiler was the Schwarzlose M1907, another almost forgotten weapon 😉

I was under the impression that the Type 99, besides from the change to the larger caliber, was also designed without the oiler since it had been identified as a source of problems in the Type 96, but I might be wrong in this regard.

Breda tried hard to sell this over-engineered mess to several nations. There were no takers which is hardly surprising!

Yeah. I built a few of these from 7.35 parts sets. None worked worth a damn with either military ammo or reloads with the original bullets loaded to the oriinal velocities. Their method of operation is more aptly described as “short cycle”.

The Breda 1937 in 7.92x57mm was however an excellent machine gun and often used by the British and commonwealth forces in North Africa especially on the long range desert raiding groups ( the fore runners to the SAS).

Seems to be an Italian thing , inconsistency. The M1838 sub machine gun another excellent weapon.

Yes, the Modello 37 heavy mg was a reasonably serviceable, but I wouldn’t be so enthusiastic about it… Besides, it also used an in-built oiler and an outdated (when it was delivered to the Regio Esercito) feeding system.

As for the M 1938 smg, I fully agree.

Mike – “the fore runners to the SAS” – The SAS was founded in WW II in North Africa, operated extensively there, was later disbanded, and then reformed.

The histories describe them as using at least one “Breda”, although I’ve never seen a clear photo of them with it so I’m not sure what model it was. However, I did read that they had problems with cold desert nights in North African occasionally causing the to oil in their Breda to become too thick for the gun to work reliably.

Both sides had long and tenuous supply lines operating at the limits of their abilities, and used whatever they could capture from the other side as generally something was better than nothing. The British used Italian machine guns because they captured loads of them, along with large stocks of ammunition. That’s not a recommendation for any particular gun however.

The description of the action reminds me a bit of the Schwarzlose…

Typo sorry 1938

Sorry for an essentially Off-Topic post, but it’s the mention here of the other Breda that made me write.

Hmm, a Breda 37 in 7.92 mm x 57? Perhaps some late-war German re-work, somewhere in Northern Italy, but not in North Africa. Those that I have researched were all chambered in Italian 8 mm x 59RB – the FIFTH Italian machine gun round used at the same time in the field, and THIRD of these in 8 mm, the others being 6.5 (Mod.914 and 935 Revelli MG, most Mod.930 LMGs) and 7.35 Carcano (late Mod. 930 LMG), the 8 mm Austrian (captured Schwarzlose, extensively used) and 8 mm French (WW1 Hotchkiss, plentiful enough to warrant Italian ammunition manufacture). What was the most mind-boggling of the big Breda was the manner of extraction – with empties placed back in the Hotchkiss-like rigid feed strip. Nice and tidy, but completely pointless and a jam-factory built-in. The Modello 937 had a tank version, Mod.938 which was box-fed from the top and ejected empties into a sack under the receiver, though.

The Breda 37 of the Portuguese contract were in 7.92×57. And yes, that extracting system was a direct invitation to trouble in the field.

Why did the Portuguese choose the Breda heavy mg over much better Browning desings(including US and Polish made guns) is not known, but we can guess…

I had the chance to shoot a Portuguese 8×57 Breda heavy a while back, so I know they exist.

OK, so there were 8×57 Bredas, my bad – but Portugese, not Italian. And in Portugal, not in SAS in North Africa. An odd-ball export contract to a neutral country that leant towards the Axis (that’s why they didn’t chose Brownings – the only Browning clone making Axis country was Japan, and these were the .50s, AFAIR. US was still neutral then, but leant to the Allies, Poland was occupied, and so was Belgium. The only European Browning maker left standing then was Sweden, and not very eager to part with any good machine gun they could post along northern and eastern border). The Portuguese were severely shortchanged in their ordnance procurement then – they not only get the Bredas 37 (actually they were m/938s, if memory serves me well), but they got as bad as MG 13s from Germans. And 98ks and P08s, and Steyr 34s and everything that was found lying around useless. Well, the sardines equity was not high these days, and that’s about all Portugal had to offer.

Well, they had plenty of tungsten ore too and the Germans were willing to pay high prices for that during the war, especially after 1942…

As for the Breda 37 (yes, the local model designation for their 8×57 version is indeed m/938), I am convinced that politics weighed a lot, being the main reason why the Portuguese military decided to buy such a thing (well-placed bribes may have had something to do with that too…), but they did so BEFORE the war: the selection process and the contract were done with by early 1938 and the order was fully delivered by 1939. The Polish-made Browings (wz.1930 in 8×57) were considered and evaluated (with very good results, if I may add) in 1937, long before the invasion of Poland. The other reason why water-cooled Browings weren’t acquired might be related to the fact that FBP was busy building their own, unlicensed Vickers clone in the newly adopted 8×57 caliber, the FBP m/939 (they had already made a few hundred in .303 in the early 30s).

Interestingly, FN-Brownings for aircraft use were also bought by the Portuguese army air arm in the late 30s.

As for MG 13, it was a makeshift choice, made after a deal with Czechoslovakia for ZB30 lmgs, intended to complement and eventually replace the Madsens, fell victim to a series of misunderstandings between the two contracting parties in the summer of 1937. The MG 13s (also designated m/938 or, to use it in full, ‘metralhadora ligeira Dreyse 7,9mm m/938’) were also all delivered before the war.

while discussing Italian machine guns one must remember that these were made by anyone but gunmakers – FIAT was automotive company, SIA built aircraft engines, Breda was making steam-powered locomotives.

Anyone have a guess why Beretta never had a hand in this field?

I would suspect they were at capacity building rifles, pistols, and SMGs.

Breda was a huge industrial conglomerate that had interests in mining, besides from a series of manufacturing divisions (not just railway rolling stock and engines): shipbuilding, electromechanical goods, agricultural machinery, motorcycles and vehicles (including trucks), aircraft and, ok, a wide range of arms from rifles and machine guns (whose production was concentrated in their Brescia facilities) to AA automatic cannon, not to mention combat aircraft (both own designs and others, built under licence). And I probably forgot something!

It was not unusual for machine guns to be made by companies who were not normally in the arms business. In Canada, Inglis made steam engines for ships, but in WWII they also made Bren guns, Browning Hi Power pistols, Boys rifles (anti-tank rifles), Browning machine guns (possibly for aircraft?), and Polsten 20mm cannon. They supplied a large proportion of the needs for Commonwealth armies (as well as other countries like China). After the war they became a major manufacturer of appliances. Rifles and Sten guns however were made at the government arsenal at Long Branch.

Arms tended to be a very cyclical business, so even arms companies had to find other lines of business when there wasn’t a war on. BSA (Birmingham Small Arms) was also at one time Britain’s largest motorcycle manufacturer.

There are some really good photos at the following sites:

http://www.pbase.com/mrclark/inglis_factory_

http://www.pbase.com/mrclark/long_branch_factory_production_photos

to make guns on industrial scale is one thing – and it is best illustrated by US automotive companies churning out zillions of guns during WW2

but DESIGNING NEW GUNS requires some specialized background and expertise, in my humble opinion