Today I am concluding our series on the standard-issue Lee Enfield system with the No5 MkI – the “jungle carbine”. Developed in 1943 as a shorter and handier pattenr of rifle than the No4, the carbine went into production in 1944 and saw use during World War Two. It featured a number of lightening cuts, as well as a shortened barrel, conical flash hider, side-mounted sling, 800-yard sights, and rubber buttpad. Unfortunately, the No5 was beset by a problem of “wandering zero”. A significant number of the rifles failed to properly hold zero when they were widely issued. The problem was never fully resolved, but appears to have been the result of receiver flex due to the lightening cuts. Efforts to fix it were essentially abandoned, as it was recognized that a new self-loading rifle was going to be adopted soon, and it would be a waste of time and money to continue development of the Lee Enfield by that point.

Related Articles

Bolt Action Rifles

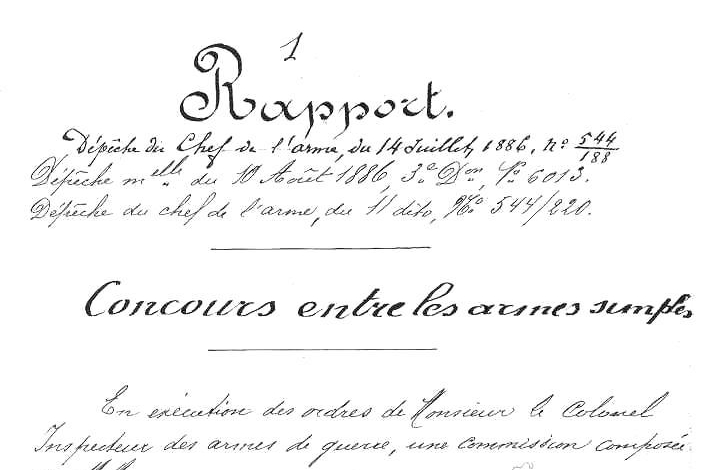

Belgian 1886 Rifle Trials Report (Translated to English)

Our friend Thibaud has spent some time translating a report from the Belgian 1886 rifle trials into English – thank you, Thibaud! He notes that the text has a lot of specifically Belgian terminology and […]

Bolt Action Rifles

The First SMLE Trials Rifles: Lessons From the Boer War

In the aftermath of the Boer War, the British military needed to address critical issues of practical marksmanship with its troops. The Long Lee rifles it had deployed to South Africa suffered significant problems in […]

Prototype

BSA Prototype .45ACP Pistol at James D Julia

BSA (Birmingham Small Arms) was the largest private arms maker in the UK during World War One, and when the war ended it of course saw its huge military contracts evaporate. One of BSA’s efforts […]

Great video sir. Thank you.

Ian, turns out your robotic relatives are quite distracting. Hopefully you can introduce them in a future video, I bet they can take the recoil of the No 5 quite well.

Thank you so much for explaining the precise findings of the wandering zero, as well as the fact that it did not affect all rifles. One wonders if the Brits were so certain about the rear receiver scallops why they simply did not add those few ounces back to the receiver & carry on production – or was it they only suspected that was the problem, but they couldn’t quite nail it down?

so it did exist, but it was also a convenient excuse to ditch it for an em2 or slr.

Imagine those little irons surplussed and sold to an enterprising dealer who could convert them to .280 Enfield. Civilians would have lapped them up even if the zero sometimes went AWOL.

The “wandering zero” was found to be a half myth concocted by SOME soldiers who experienced the problems of barrels and stock-nodes not matching up when final assembly of rifles was done half-baked. The rifle design didn’t produce a “wandering zero.” It was BAD manufacturing that did the thing.

It will definitely leave a mark on your shoulder.

I have a Rifle No. 8 (.22 LR trainer) built in 1949 on a No. 5 receiver.