I previously reviewed a book on archaeological study of the Little Bighorn battlefield, which did an excellent and very insightful job of tracing the battle through tangible artifacts, including forensic tracing of different individual weapons across the field. I recently picked up another book on the battle (Little Bighorn to the Americans; Greasy Grass to the Sioux and Cheyenne). This work takes a very different approach to the history: following the stories from the descendants of the combatants who were there that day. The author, Wendell Grangaard, is a 53-year resident of the Dakotas and an avid historian. His work as a construction crew chief in the area put him in contact with many Sioux and Cheyenne, including (instrumentally) Benjamin Black Elk, whom he first met in 1967. Benjamin Black Elk was an iconic Sioux historian, and his father (a cousin of Sitting Bull) had been one of the warriors at the Greasy Grass.

I previously reviewed a book on archaeological study of the Little Bighorn battlefield, which did an excellent and very insightful job of tracing the battle through tangible artifacts, including forensic tracing of different individual weapons across the field. I recently picked up another book on the battle (Little Bighorn to the Americans; Greasy Grass to the Sioux and Cheyenne). This work takes a very different approach to the history: following the stories from the descendants of the combatants who were there that day. The author, Wendell Grangaard, is a 53-year resident of the Dakotas and an avid historian. His work as a construction crew chief in the area put him in contact with many Sioux and Cheyenne, including (instrumentally) Benjamin Black Elk, whom he first met in 1967. Benjamin Black Elk was an iconic Sioux historian, and his father (a cousin of Sitting Bull) had been one of the warriors at the Greasy Grass.

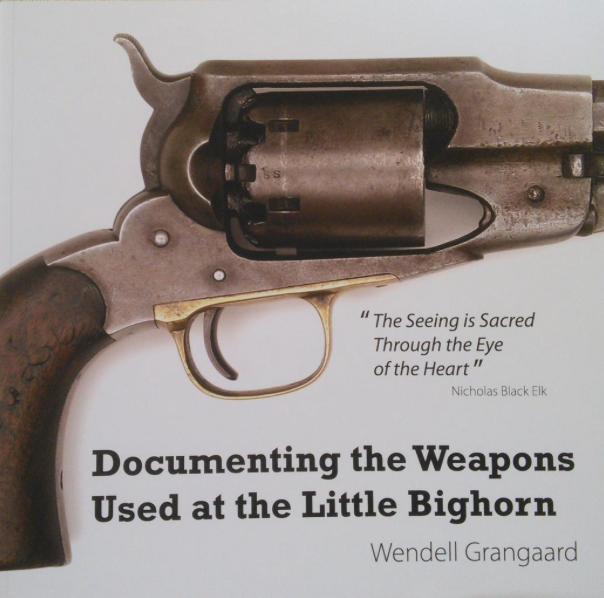

Through Black Elk and others, Grangaard compiled a collection of battle accounts of that fight and the others before and after it. His interest in firearms led him to combine these oral histories with detailed research on the arms carried by both the tribes and the whites at the time. The result, in the form of this book, is a retelling of the battle with a focus on the arms used, and with numerous photos of the specific weapons carried, captured, and lost that day. More importantly, Grangaard’s lifelong friendship with the tribes and interest in their customs has allowed him to present the warriors’ accounts in an objective light, explaining actions like the mutilation of bodies and the use or non-use of captured arms from the battlefield. The Little Bighorn stands out from other battles because Sitting Bull had decreed that the weapons of the fallen whites should not be taken on that day, which made for a substantial dilemma for the warriors. Many took arms anyway, but they often treated them as the property of Wakan Tanka and kept them wrapped up and hidden. Guns captured at the Little Bighorn were rarely discussed or seen in public, unlike arms from other battles, which were treated as rightful and glorious spoils of war.

At any rate, Grangaard has done a fantastic job in this book of presenting the individual battle accounts with the event on the large scale, and allowing us to understand what the day was truly like for the Indian forces there. The book begins with some introductory explanation of Sioux and Cheyenne culture as well as US Cavalry organization. It then moves into brief descriptions of the events that led up to the Battle of the Greasy Grass, including the Fetterman Massacre (the Battle of the Hundred in the Hand) and the Rosebud Battle. Each of the 21 accounts which follow includes a map showing the warrior’s movement through the day, and also what is known of the man’s life after the battle. In more than one case, he is able to trace specific individual firearms from original issue to the Cavalry to their capture on the field and through to surrender on the reservations years later or to present-day ownership. The combination of macro and micro views of the fight from a writer with a nuanced understanding of both sides makes this a fantastic and engrossing read.

The book is not available on Amazon, but can be purchased through Abe Books or directly through the publisher, Mariah Press. Or you can do what I did, and pick up an autographed copy from the gift shop of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. But however you acquire it, this is an excellent book for anyone who is interested in firearms or the history of the American West – and if you enjoy both subjects, you will find few books more interesting than this one!

If that’s a Remington 1858 New Model Army on the cover I have a reproduction I bought back in the 1990’s.

The several seasons of field-work in the 1980s at the Greasy Grass/Little Bighorn battlefield where the artifacts could be used with a computer model to suggest how the battle proceeded, what weapons were used, etc. has become something of a model for battlefield archaeology.

Similar techniques were used at a survey of the Palo Alto battlefield in the early 2000s too.

There is an interesting book by historian Gump (no relation that I’m aware of!) called _The Dust Rose Like Smoke_ that tries to compare Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass and Custer’s 7th U.S. cav with the British defeat at Isandlwana in 1879.

both caused by senior officers poor judgment amounting to stupidity, nothing changes as I have observed thro my 22 years of service thro South Atlantic, NI, Bos, Kos, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Have you read the reprint of the interview with the warrior Rain In The Face? I was reprinted in an outdoor magazine – IIRC, Field and Stream – some years ago. Not sure if it was F&S.

I recommend Red Sabbath: the Battle of the Little Bighorn, by Robert Kershaw. Kershaw examines the Fetterman, Greasy Grass and Rosebud battle from the perspective of a conventional military force confronting an insurgent force with an unexpected will to fight and an unexpectedly sophisticated weapons.

There is a book available for free through Google Books that has an account of he battle as told by American Horse, with his tongue loosened by whiskey. American horse gave no formal accounts of the battle to historians. e got drunk one night and finally “opened up”. His account recorded over 100 years ago so closely matches the recent computer renderings that it is scary!

Many Indian rifles that were later surrendered are on display at the Browning Museum located on the Rock Island Arsenal.

It seems that an inordinate amount of weapons of undocumented lineage sold on gun auction sites are claimed to have been used at that famous battle. Excavations of fired casings have enabled some of them to “forensically prove” that at least several such claims aren’t just rural legends. But something I’ve got to wonder about is this: forensic science being what it is (as least as much art as science) what happens to someone who throws down a six-figure sum to buy such a rifle from a RIA or James Julia auction — only to have experts a decade later, using improved technology, dispute its authenticity — an authenticity that the buyer paid a 50x or 100x premium for?

The Little Bighorn battle is not only one of intense interest, but a notable “military” battle in US history where the weapons used by the winning side were largely undocumented. The major art auction houses in the world are said to invest considerable money to verify an artwork’s authenticity (though many would dispute their effectiveness) but it seems that in contrast, gun auctions are much more caveat emptor.

Good grief. The saddest part is that no American survived save for the one who was sent out on an errand elsewhere just before Custer and all the guys (and all but one horse) around him were filled with lead and mutilated… The Trapdoor Springfield was good in stand-off battles at long range (where most lever action rifles of the day had a hard time since they fired “pistol” ammunition) but once the Indians got to within revolver distance, Custer’s guys were screwed. Single shot rifles are TERRIBLE at fending off opponents who get up close and personal. And if I’m right, that’s when the cavalrymen whipped out their side-arms. The problem with that was when the revolvers ran out. With no quick reload or knife available (cavalry are issued heavy sabers, which are only good when slashing victims from horseback, not when the other team drags you off the horse and into the dirt), I assume that’s when Custer started to wish he hadn’t abandoned the Gatling.

Did I mess up?

No, you pretty much summed it up.

There was no heroic “Last Stand”, as the archeological evidence shows, just a series of small massacres as small (20 men or less) groups of cavalrymen, panicked and trying to escape with their lives, were surrounded, overrun, and killed, mostly hand to hand, by superior numbers of opponents who were much better equipped for, and skilled in, close combat than the cavalrymen were.

The entire “battle” was over in about half an hour. The myth that it took longer comes from the fact that Reno’s surviving second section was pinned down for most of the afternoon and into the night by enemy sniping. They only managed to break loose when the reinforcements arrived the next morning, and that was mainly because the Sioux skirmishers had pulled out just before dawn, not wanting to find themselves in the same fix Custer had been in the previous day.

BTW, Greasy Grass is not really comparable to Isandlwana. There, the Zulu had about 20,000 troops vs. about 1,800 British, an over ten-to-one numerical superiority. And contrary to Hollywood, the 24th Regiment of Foot was not “wiped out”; they suffered about 1,300 KIA while inflicting nearly twice as many casualties on the Zulu impis (regiments). The main body forming the front line suffered the heaviest losses, including Lord Chelmsford himself, which probably gave rise to the “wiped out to the last man” myth;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Isandlwana

A better comparison to Little Big Horn would be Majuba Hill, two years after Isandlwana. There, the Boers basically destroyed a 405-man detachment of the 58th Regiment and the 92nd (Gordon) Highlanders, with only about the same number of men on their side. They killed 92 men, wounded over 140, and captured 58 for the loss of one dead and five wounded on their own side. It was the most one-sided defeat the British Army had suffered since the American Revolution and the War of 1812. (See “Concord and Lexington”, “King’s Mountain”, and “New Orleans”; Khartoum was still in the future at this point.)

In the case of Majuba, armament on both sides was roughly equal. Simply put, the Boers were better tacticians;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Majuba_Hill

Which is also the point of Little Big Horn. By all accounts, Tashunkta Witco (in English, “Horse which is crazy”, i.e. Crazy Horse)was a much better combat commander than George Armstrong Custer.

cheers

eon

“Including Lord Chelmsford himself.” Actually, no. Lord C was not present during the fighting at Isandlwana, he was leading a separate force that was not involved in the battle that day. When news of the disaster reached London Lord C was relieved of command and replaced with Lord Wolseley. However, by the time Lord W actually got to Africa to relieve him Lord C had hustled up to Zululand and won the battle of Ulundi, shattering the Zulu military and forcing Chetswayo to surrender. All was forgiven.

The 24th Foot was the sister Regiment to the Rhodesian African Rifles, a Regiment in which I had the privilege of serving.

Wafa Wafa, Wasara Wasara.

The sword used by US cavalry at the time was the Model 1960 light cavalry sabre, which weighed only 2 lb 4oz, so not excessively heavy at all and a much better close combat weapon than any knife ever invented except at cramped spaces. I don’t know how much training on foot the US cavalry received with their swords, but the most important factor is that Custer’s men were typically outnumbered at the close combat stage, which is very bad unless you have trained to fight in tight defensive formations with your weapons. Only in movies people attack one at the time. Only infantry typically received such training, and with bayonets rather than swords in the 19th century. The native warriors also had spears, which in most cases are better weapons than swords for unarmored and shieldless combat.

When you said “heavy cavalry sabres” you probably thought about the Model 1840 heavy cavalry saber, which weighed 2.5 pounds, affectionately known as the “Old wrist breaker” by US cavalrymen. That was fairly heavy sword for a single handed weapon, although far from unusable even on foot. For comparison, the medieval single-handed arming swords weighed about the same or slightly (1.5oz) less on average, and they were the most popular swords for several hundred years.

Were US cavalrymen of the era, outside officers, taught to fence, which skill would be more useful on the ground?

Perhaps the skill of feinting a lunge, where you trick your opponent into defending against a blow that never comes!

Correction: Feigning, not feint. In any case, saber fencing skills would do you no good against a mob unless you impaled one (in such a manner as not to kill him instantly) and used him as a shield!

I wouldn’t say that they would do you “no good”. Knowing basic saber fencing techniques would certainly help a lot, but the main problem would still be that typical sabre fencing in the 19th century didn’t include fighting in formation with other sword users (infantry officers were taught how to use their sabres alongside bayonetted muskets/rifles), nor did they include fighting more than one or at the most two opponents in front of you. Such skills became largely unnecessary after the 16th century in typical European style warfare.

Fencing isn’t much use against Indian rifles, arrows, even spears. Outnumbered badly as they were every soldier a swordsman would have made zero difference

FYI the 7th Cavalry did not carry sabers in the Little Bighorn battle. Jjonathan

A bunch of Americans survived that fight. They just weren’t white.

single shot rifles are terrible at…… Waterloo? Single shot rifles place a premium om choice of ground, tactical nous and discipline, therein lies yr real problem, as it still does.

AA,

Good question about validation and verification for authenticity. Let me tell you an odd story, but true…

‘Twas in the 1980’s and I was visiting my little brother in Lincoln, Nebraska. A hot summer night and we’re having a beer on the porch when the brother says, “Hey, you should meet my across-the-street-neighbor. He’s an interesting guy…”

He calls out to his wife, “Hey, we’re going over to Doug’s house.”

And guess who Doug is? Yup, Doug Scott, author of the archeology book on Custer at the Little Big Horn. He’s a personable fellow and shows us his top floor really, really interesting home office, replete with Old West Army uniform, period firearms and real-deal Native American weapons. I emphasize, Real Deal.

How do I know? Among the period stuff in the room is a very expensive and modern comparator microscope. For those that don’t knonw what that is, it’s the instrument investigators use to compare bullets and cartridge cases to prove “this” bullet came from “that” gun. Analysis of the cartridge case verifies way beyond reasonable doubt that this particular cartridge case was fired from that particular rifle.

“The Nebraska State police were kind enough to let me borrow this,” said Doug, “But let me show you something really interesting.

He produces an original 1866 Winchester. “We got this from a Native American family reputed, as long as any family member could recall, that it had been at the Little Big Horn fight. We managed to find several live cartridges for it, harder to find, in fact, than the rifle itself. They don’t make .44 rim fire ammo much anymore.

“We fired one off into a water-bath so the bullet would be undamaged and the began searching for its mate.”

He installed the newly fired bullet into the comparator.

“We found not only this bullet on the battlefield, but this cartridge-case not too terribly far away,” he said as he installed the 1876 fired bullet in the comparator.

He fiddled a bit adjusting the instrument and then said, “take a look…and give me your honest opinion if you think this could possibly be a match.”

Now I’ve seen some interesting and even unusual things in life, some even confounding, but few things can match what I saw through that comparator. My hair actually stood on end. It takes a pretty powerful object to cause that in me.

“And that, Sir, would stand up in any court in the land,” said Doug Scott. And it certainly would.

So there you go. That’s how verification can happen.

And should you ever have the chance, like Waterloo, walk the battlefield. It clairifies exactly why things worked out the way they did.

I had the pleasure of taking some forensic classes with Doug’s wife and got to meet him on several occasions. I was even invited to his house for a couple of university mixers. I can vouch that his man cave was extremely impressive and overflowing with Wild West/Frontier artifacts. He even had a cannon in his garage! Fascinating guy and I am glad that I had the chance to meet and talk with him.

One of Wendell Grangaard’s auctions at Julia in Spring 2014 was of a ‘hand made tomahawk’ he claimed came from Little Big Horn battlefield & belonged to He-Dog which he used to finish off Custer & his men. Any knowledgeable collector would know immediately it was an African Axe–looks nothing like our tomahawks! How did he verify all this? Because of the 5 holes in the blade–seriously. That was it. As an authenticator of tomahawks I have little knowledge of his guns but there are many others questioning his stories of guns that were sold the month before without provenance & suddenly have reappeared with the same serial numbers purported to be from Little Big Horn’s battle with specific owners names in the next months auction at another auction house. Follow the money. http://www.thetruthaboutguns.com/2014/10/robert-farago/rock-island-auctions-distances-james-d-julias-fake-guns/

gunsofhistory auction could be the biggest fraud case in history,bought an item at auction and the smithsonian says grangaard is hallucinating,item is fake,i see a huge class auction suite coming against him an auction site

I will be most interested in what happens. AS a collector of Smith & Wesson Model 3, specically the first thousand sold to the US government and distributed to the 2nd-7th cavalry, I purchased the auction one that was said to belong to Vincent Charlie of the 7th and captured by one of the Indians when Charlie was killed. The detail pictures of the markings on the gun were published but when I received the gun, with the aid of magnification, I could not see the markings. A call to the number given to me for Mr Granguaard’s did not het a call back. Neither did the second call. While this puts a shadow over this S&W, serial number 1341, it is definitely one of the first 1000 and therefore could have gone to the 7th. I am told that a specific list of what specific gun of the 1000 went to which location does not exist. So for my use, it is what I collect. I am most curious as to ifd it actually was Vincent Charlie’s and was at the Battle.

Considering how famous the site is, and how often visited, I’m surprised that enough brass has survived in place to allow for forensic mapping of the battle.

I’ve read that there were grumblings about the Colt revolvers, versus the Schofield Smith and Wessons that a few cavalry regiments were issued at the time. With automatic ejection, it might have been possible to keep enough volume of fire to survive and withdraw. Might.

Whenever Custer’s Last Stand crops up, someone will mention those missing Gatling guns. Custer left behind a quarter of his personnel, his command’s sabers, anything that would slow down his troopers (supply wagons, ambulances), and his artillery battery–the latter included three-inch rifles and Gatling guns.

The 1876 Gatling gun was an artillery piece and of little value to a mobile column engaged in counterinsurgency. Finding the elusive guerrilla fighter was difficult and then the guerrillas had to be fixed into place long enough for the artillery pieces to be brought up from the rear. Once dragged into position, the gun had to be detached from the limber and put into action–this took minutes at best. A running man can cover 100 yards in less than 30 seconds. Three minutes means that the man has gotten at least 300 yards away, possibly half a mile away. The Gatling gun was ineffective beyond a quarter mile against point targets but could be devastating to an area target such as an infantry company forming a firing line or hollow square. When did the Sioux warriors form a Napoleonic infantry formation? The last group that may have did that, the Aztecs, were slaughtered by the Spanish.

Now back at the fort the Gatling gun and the other artillery pieces might have did some good, keeping large groups of horse-mounted warriors at bay–but in the field the targets were fleeting and small and by the time the Gatling gun was dragged up, unhitched and ready to fire there was no target left.

Those three-inch rifled cannon had greater reach and more effect beyond the quarter mile mark than the Gatling gun. Again, no targets. Shell a tent city? The Sioux didn’t fortify, relying on mobility–and it worked. The Sioux weren’t really defeated on the battlefield but lost due to severed logistics chain–they couldn’t both fight and conduct their tradition of hunting and gathering.

Leaving behind a quarter of the command’s personnel is still common practice. The size of the Army rifle squad was predicated on having only 80% of the squad present for duty while still remaining combat effective. The ash and trash stories soldiers tell are still shocking–going into battle with only half the platoon to take a company-sized objective because everybody else was detailed away. And that was before the shooting began!

Any body really need to be told about the cavalry saber in guerrilla warfare? Most of Custer’s command did have knives, ranging from large Bowie knives to pocket folders or their dinner knives. Accounts from the survivors speak of digging trenches with those knives–there were no entrenching tools provided. Cavalry did have the carbine but carbines up to 1945 (yes, World War Two) were not provided with bayonets. Cavalry had the saber until sometime in the 1930’s and other than for ceremonial use the saber was practically useless from about 1863 (middle of the American Civil War) on–Confederate cavalry learned to use multiple revolvers and even shotguns from the saddle, and mounted guerrillas on both sides got out of the sword play habit for a number of reasons. European and South American lancers were still in vogue at the time–but the mounted guerrilla lasted in the United States to at least 1892–yes, post-Civil War. Jesse James and his gang were among those post-war guerrillas still fighting the Yankees.

I don’t think any machine gun team members are reading this or they’d comment on flank and rear security for the Gatling guns–at Custer’s Last Stand, there wasn’t anything that could be called a firing line, and no protection for flanks and rear.

But one thing that the Gatling guns might have accomplished is to slow Custer down enough that he missed his date with destiny.

Like most of us interested in “Custers demise at the Big Horn”…I truly believe there is so MUCH “embellishment” on what actually occurred is what keeps this SAD battle’s history a constant subject in movies/books and related articles. Try this one out and see IF it fits historically….I recently met a “collector” of weaponry especially involving the Custer 7th Cav. issuing about 20 +/- Springfield Carbines 45-70cal. to Indian Scouts as I recall him stating were CREE nation(?)…these alleged scouts having these Spg’fld Carbines then proceeded to embellish them into a “tribal SPIRIT GUN” The markings on the R.side of the rear of stock consisted of a 5 pointed star(lines) emitting out from a small circle–all meeting at an Outer circle” Apparently several were confiscated from the battle of fallen scouts by the Lacota(Sioux) nation. I personally have observed about 5 of these so-called Spirit Guns on display at a Bank in Red Wing,Minnesota which is a city of 16,000 near the reservation of the Prairie Island Sioux nation. Whether or not these are VALID historical weapons-I know not…but they are interesting Springfield Carbines to wit…Perhaps some Native American can verify or refute such as to my way of deducing this NO combatants survived to tell WHAT actually occurred on that day…and WHY weren’t these Springfield’s Spirit Guns bantered about previously..or at least some reference/provenance to validate them…Stay tuned..! In parting I am truly amazed at the lack of military planning to enter into a conflict as this magnitude knowingly had many US Cavalry defeats in confronting the various tribes of the Great Basin-Plains…??

Seriously? Sabers would have been about as much use as a kitchen broom. The Indians chose to close to close combat range to count coup. Not being stupid if a solder was standing there with a long knife rending them off, they just would have shot him. They had plenty of arrows and captured weapons and ammo.

As it was over half of Custer’s men went down with Keogh and his three companies EAST of the ridge. Custer and his two companies went down WEST slope of Last Stand Hill or down in Cemetery ravine. None ever made it to Deep Ravine despite myths to the contrary. A saber wouldn’t have been much good for terrified running troopers being run down by warriors on foot or on horseback.

By the time the six survivors from Keoghs companies arrived on Last Stand Hill the jig was already up and likely they continued to ride or were gunned down on the hilltop silhouetted on the skyline from fire from the North, East and West while they sat stunned by the carnage they saw on the hill slope below them.

Maybe their arrival and subsequent flight down the hill gave impetus to the flight of 28-40 men down the hill toward Deep Ravine that so many Indian accounts mention. Regardless of the timing or cause. There are a lot of markers down on the south walking trail along the line many call “the south skirmish line.” Way too many to have been from Company E alone. If following Cavalry doctrine one company would have been sent forward and the other, probably Co. F kept in reserve with the Custer and his command group.

I an reminded of the scene in Band of Brothers when they were attacking the German occupied village and the attack falters and MJ Winters wants to go down and lead in the attack but is restrained by the presence of Col.Sink. He then without missing a beat calls for Lt. Spiers to run down relieve Incompetent Lt. Dike and take the attack on in which he does. It illustrates the difference between command and leadership. George might have been a great leader but by going with the two companies forward he essentially abrogated is role as commander by getting too close to the action and being cut off from the majority of his command. He lost control of the battle and all but a portion of his men early on.

This guy is definitely selling fake items from little big horn. You can’t even find anything from his books hor history on this language that this guy claims to understand. I’m guessing he set this scam up years out and is hoping to cash in on this now. Run don’t walk.

single shot rifles are terrible at…… Waterloo? Single shot rifles place a premium om choice of ground, tactical nous and discipline, therein lies yr real problem, as it still does.