After several years of work and at least two Swiss military trials, Louis Schmeisser’s design of the Bergmann self-loading pistol was still not quite good enough to become a commercial success. Only a few pistols had achieved this goal, though, and the market was still wide open for anyone who could perfect their design. As I mentioned in Wednesday’s post, the model 1894 Bergmann No.1 was effectively a transitional model leading to the 1896 version of the Bergmann.

The No.1 had made the pistol a straight blowback action, with a recoil spring located underneath the barrel. In 1896, Schmeisser changed this configuration, moving the spring into the back of the bolt assembly (where it would remain throughout all the rest of the Bergmann pistol variants). This was a more efficient use of space, as the forward position of the magazine defined the minimum length of the pistol. This space could be used to house the mainspring, encircling the firing pin (but not acting on it directly). This also allowed the firing pin to act as a mainspring guide, preventing it from kinking during assembly or disassembly. When looking at pistols, this change makes differentiation of the 1896 vs 1894 models simple – the later guns do not have a housing under the barrel to hold the spring.

The model 1896 pistol was made in three different calibers: 5mm, 6.5mm, and 8mm. This discussion will stick to the 5mm guns, which were designated No. 2 by Bergmann. These No. 2 pistols were produced at the same time as the 6.5mm (No. 3), and share a single block of serial numbers. Between the two models, approximately the first thousand guns made maintained the extractor-less design of the No. 1 – but it soon became apparent that this was a liability. While extraction was generally reliable, the lack of an extractor meant that there was no easy way to remove a case that did become stuck for any number of reasons. In addition, the extractor in a blowback pistol has a secondary function of controlling the position of an empty case to ensure it hits the ejector at the proper angle to eject cleanly. This was a flaw in the early Bergmanns, as cases could hit the ejector at odd angles and fail to clear the action, causing malfunctions (and consider the clearing process, given that without an extractor you cannot retract a partially fed round by pulling the bolt back).

With all of this in mind, Schmeisser added an extractor to the 1896 Bergmann design after those first thousand of so guns. This of course also required a change in the ammunition to use a cartridge case with an extractor groove. That was simple enough, as all the rest of the geometry of the 5mm Bergmann case was retained, including the significant taper of the case (which was instrumental in allowing easy and reliable extraction, as the slightest rearward movement of the case in the chamber would remove all contact between case and barrel). In both the early and later versions, the 5mm Bergmann fired a 35 grain FMJ bullet at 580 feet/second. The ammunition was manufactured by DWM, and early examples used a cannelured bullet and full crimp while later production eliminated the cannelure and used a 3-point stab crimp. In DWM’s catalog, the cartridges were identified as #416 (early, no groove) and #416A (late, with groove).

Ballistically, the 5mm Bergmann is one of the weakest cartridges produced aside from gallery or Flobert type rounds. It had about half of the velocity of the contemporary 5mm Clement, and about 60% as much muzzle energy as the .22 Short (26 ftlb). I still wouldn’t want to be shot by one, but it was clearly outclassed even in its own day. Sales reflected this, as it was less popular than the No.3 Bergmann (in 6.5mm). On the other hand, the options for a quality pocket semiauto were very limited in 1896, and the No. 2 was reasonably popular with between 1,500 and 2,000 being sold in Europe and beyond. Wilson is a bit contradictory in his assessment of the cartridge, claiming both that it has both “considerable penetration” and yet also a tendency to be insufficiently stabilized and to keyhole at 20 feet.

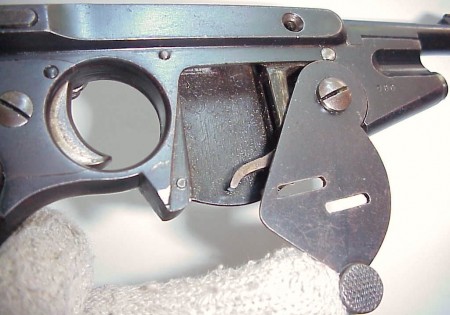

Loading the No.2 Bergmann was the same process as the No.1; the magazine was accessible through a pivoting cover plate on the right side of the pistol. It would hold 5 rounds of ammunition, typically carried as a single unit in a Mannlicher-type clip. A follower finger in the magazine (rotated out of the way when loading) would push the cartridges up, and allow the clip to fall free through the bottom of the magazine when empty.

Ejection on the No.2 was vertical, out the top of the action. Unlike the larger versions of the 1896 design, the No.2 did not have a protective cover over the ejection port – probably because the pistol was too small for this to be conveniently made without being too flimsy. One other feature unique to the No. 2 was the option of a folding trigger. This was not an uncommon design element in period revolvers intended for pocket carry, but it was unique in selfloaders.

One other interesting feature of the 1896 Bergmanns is that their barrels are easily removable. In the above photo, you can see a screw above the trigger – this is what retains the barrel. Remove that screw and rotate the barrel 90 degrees (the barrel’s positioning lug is visible right above the patent text), and it comes off. This allows for easy cleaning, since access to the breech would otherwise require removing the bolt completely.

One final note – I have found photos of about a half dozen different No.2 Bergmann pistols (these three from Julia being the best quality photos), and every single one of them is marked “611” on the left side of the barrel. The actual serial numbers are on the right side, in front of the magazine. I have no idea what the 611 marking indicates, but a different number is used on other caliber 1896 pistols (the No.3 and No.4).

Technical Specs

Caliber: 5mm Bergmann

Bullet Weight: 35 grains

Muzzle Velocity: 580 fps (177 m/s)

Clip Capacity: 5 rounds

Overall Length: 11 in (280mm)

Barrel Length: varies, typically 3-3.5 in (75-90mm)

Weight: 36.3 oz (1.03kg)

Action: Straight blowback

References

Ezell, Edward C. Handguns of the World. Stackpole Books, New York, 1981.

Reinhart, Christian and am Rhyn, Michael. Fastfeuerwaffen II.

Wilson, R.K. Textbook of Automatic Pistols. Samworth, 1934 (reprinted by Wolfe Publishing, Prescott AZ, 1990).

One thing you did not mention about the need for extractor is removing a live round from the action when you are just trying to clear the gun. Many blow back 22LR action do not require an extractor but have them for this reason. I broke my extractor on my Ruger Mk2 during a match and did not notice until I went to clean the gun. It functioned flawlessly during the match w/o the extractor.

Sounds like a problem some people don’t know about. Many blowback pistols without extractors have a barrel hinge near the muzzle so that in the event that a cartridge fails to eject itself, the user can clear the chamber manually after tipping the barrel up. Either you get a paper clip or something to yank on the rim (or extraction groove) or a really long and thin stick to ram the spent cartridge out. Does this sound close to the procedure done in real life?

La Francais pistol

http://world.guns.ru/handguns/hg/fr/le-francais-e.html

is a extractor-less pistol with hinged barrel, the case was extracted only by gas-pressure, so when it fail it must by done manually for example using cleaning rod. Due to its construction, it must be loaded with magazine and cartridge-to-chamber separately – manually cycling is not possible.

Some Berettas had this arrangement, as well, notably the Model 950 pocket auto in .22 Short (!) and the later Model 20 “Bobcat” in .25 ACP. The bigger double-action Model 86 in .32 and .380 ACP also had such a “tip-down” barrel.

Beretta’s reasoning was that such weapons were often used by women as defensive pistols, and since the ladies might not have the hand strength to rack the slide to load from the magazine, they could just load the barrel separately, like a break-action shotgun.

While the 86 might seem a bit big for a “lady’s gun” by 1970s European standards, it made excellent sense as a house gun then and there. Also, back then, most European police agencies issued .32 or .380 autos to their uniformed officers, so the compact Beretta with its double-stack magazine holding 13 to 14 rounds made good sense for the flics as well. (I’m not an enthusiast of .32s or .380s, but if I found an 86 I could afford, I’d buy one today.)

The Le Francais pistols were made in several sizes and calibers, ranging from the small “Modele de Poche” in .25 ACP on up to the “Type Armee” in 9x20SR Browning aka 9mm Browning Long.

The latter was about the size and weight of a P.08 or P.38, but hit more like a .38 Special than a 9×19. (Mind you, that’s generally enough if you hit the target in the right place.)

Most of the bigger Le Francais weapons had a tubular “loop” on the magazine floorplate, for the extra round you were supposed to load the chamber with.

In all versions, the Le Francais pistols were striker-fired, and most of them were DA-only on roughly the same principle as the later Heckler & Koch VP-70 series.

In many ways, the Le Francais pistols were half-a-century ahead of their time. Imagine a “Type Armee” produced today, in 9mm Ultra/Police with a double-stack magazine and a polymer frame. I think it would be kind of neat, actually.

cheers

eon

One of the American made .22rf open bolt semi autos had an extractor fitted to the breech end of the barrel, for manually ejecting any rounds which failed to fire.

a knife blade works well for open bolt .22s which don’t have that facility – the procedure is fiddly, but I’ve yet to experience a bunny returning fire, and with the rimfire case getting hit at right accross the base with the firing ridge, failures to fire are rare.

It was the Marlin Model 50 which had some examples fitted with a manual extractor on the barrel rather than the bolt. There are some pictures up here: http://openboltguns.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/marlin-50.html

Wasn’t a Bergmann of some sort featured in the John Wayne movie “Big Jake”?

It’s supposed to be an 1896 Bergmann, but it’s actually a prop gun built on a Walther P38.

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bergmann_(Pistole) states that due to taper-case cartridge the pistol leak gas.

The mystery 611 mark might relate to the patent mark underneath it, either as a patent number or as a date stamp (on one of the guns the mark is clearly made from a 6 and an 11 stamp).

Maybe, but I doubt it. As you’ll see next week, the No.3 and No.4 pistols also have number in the same location, and there doesn’t see to be a date-related pattern to them. The number is “611” on 5mm guns, “278” on 6.5mm ones, and “156/14” on 8mm ones.

I’ve often wondered if those were factory model numbers, similar to the system later used by Smith & Wesson, Model 39, 59, etc.

Just a thought.

cheers

eon

Awesome gun. I find it looks both retro and futuristic.

Definitely the kind of semi-awkward semi-auto that was common in the late 19th century, but certainly a quality piece nonetheless. The folding trigger seems like it works fine, though it still appears to me as an unnecessary inclusion. Getting an extractor and extractor groove implemented first should have been a greater priority in hindsight, but whatevs. Most def. not a fan of the anemic cartridge – Tiny and weak, not the best combo. I guess back in those days and even up to just a couple decades ago, if you wanted a small gun, you had to take a small cartridge to go with it (I’m reminded of the Beretta pocket pistols in mouse calibers).

One other thing to think about, especially in the “mouse” calibers and anemic things like the .41 rimfire derringers is the tendency of soft tissue hits becoming infected from the clothing and dirt carried by the slugs. In the pre-Penicillin days, this was a MAJOR cause of concern. I’m quite sure the prospect of a .22 short, outside lubed, hitting me in the gut would scare the heck out of me.

I prefer to carry a .45, normally carry a .380 (S. Texas is HOT) and have a really spiffy looking .22 for social occasions where I wish to carry something in my pocket.

Never seen more toy-like pistol; I actually wonder if it was meant to hurt anyone. It is appreciated that FW brought it to reader’s attention.

Denny, the Bergmann line of pistols may look like a bunch of toys, but that’s still potentially lethal! If I lived in Europe during the 1890’s and had a Bermann in my pocket, I would use it in the event of a mugging (most muggers will probably use knives so they don’t draw armed police attention, since get-away cars haven’t been invented yet). I would get close to the mugger, pretend to pull out my wallet in order to hand it over, then crotch-kick him, draw the Bergmann and stick it in his gut, then empty my five-round clip into his innards!

Sound like a bad day to eat lead?

In the days before antibiotics and tetanus vaccinations, and when the streets were liberally coated with tetanus bearing horse crap (which splashed around in wet weather and blew like dust storms in dry)

any puncture wound could easily prove fatal, even if it took several days to get there.

I also wonder whether we have actually lost a major inhibition against aggressive violence.

Before the 20th century and its gun controls, pretty much everyone who could afford to be, went armed. The Bronte sisters clergyman father – when he got dressed in the morning, put his pistol in his pocket. People who could afford to and wanted to be seen to be armed, wore swords.

and society was more peaceful then than it is today.

If you shoot mugger and he will die due to wounds in hours or days, he has enough time to attack you.

The more important in pocket-gun is the physic effect, i.e. discourage badguy from attacking or force to retreat.

Andrew and Keith… I see you argument gentlemen and understand. One has to take a 19.century look into consideration to see it in connection. Any arm from that prospective was a good arm.

on this page:

http://www.horstheld.com/0-Bergmann.htm

the 611 is described as the model number, and if you see it on other no.2s but different on 3/4 they may be right.

Still looks as though it may have inspired Mal Reynolds’ pistol in Firefly and Serenity. Not this specific model perhaps, but the Bergmans in general.

I absolutely LOVE the Bergmann 1896 (especially the 6.5mm).

It looks like something from “A Princess of Mars”.

I too remember the reference to it in “Big Jake”, as well as the article in “Guns & Ammo” that showed the Walther P-38 with plates welded on the sides of the frame to simulate the magazine in front of the trigger guard.

I’d really like to have a modern copy in .32acp.

I have a burgmann #2 flip triger. in good shape are thire any clips for this gun

I don’t know of any place that has any for sale. You might try contacting Horst Held: http://www.horstheld.com/default.htm