On this day 138 years ago, the combined forces of the Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho tribes delivered a staggering defeat to the US Army’s 7th Cavalry under the command of General George Armstrong Custer. The battle was glorified in the East for largely political reasons in its immediate aftermath (and there were no white survivors to contest the story), and it has only been in the last few decades that the true story of what happened in that fight has become well understood. A major academic revelation (not counting the Indian accounts of the battle, which gave a pretty accurate description all along) came from a field study in 1984 and 1985 which collected and mapped thousands of artifacts, mostly cartridge cases and bullets (for a full account, the book written on the study is Archaeological Perspectives on the Battle of the Little Bighorn, reviewed here).

One of the results of that study was indisputable evidence that the Indian forces were much better armed than had been previously believed. Among the 40+ different types of firearms carried by the warriors were a large number of lever-action Henry and Winchester rifles and carbines. With that in mind (and because of his interest in frontier history), my friend Karl decided to shoot this month’s 2-gun match with a replica 1866 Winchester. He used it in place of both rifle and pistol, since handguns saw minimal practical use at the Little Bighorn (or the Greasy Grass, as the Indians called it). He isn’t shooting black powder, simply for ease of use (it was 105F during the match), but his .45 Colt ammo pretty much matches the ballistics of the original loads.

So in memory of the desperate fighting on that day, let’s see how the 1866 Winchester performs in this set of stages…

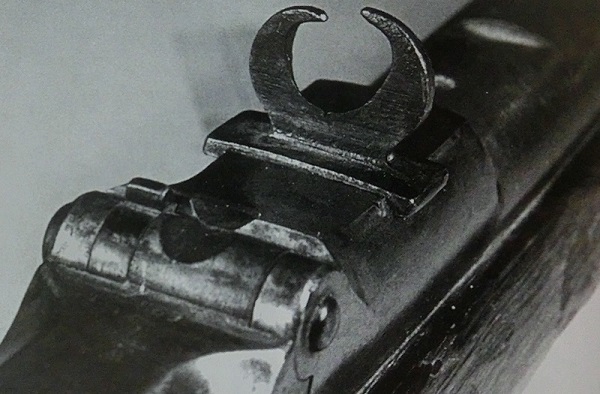

Interestingly, I happened across a photo (in Guns of the Western Indian war) of an buckhorn sight almost identical to Karl’s added to a Trapdoor Springfield:

How did his score compare to the guy with the Ballester-Molina and the M76?

I took 25th; he took 29th.

I love that you guys have a local match that will let you do fun stuff like this. Years ago I shot my 1896 Broomhandle Mauser at a small weekly indoor USPSA match. I even used a wooden stock holster. I can’t remember now if it was the red 9 or the .30 Mauser one.

That was really interesting, the speed and accuracy on the short course was really impressive and even the long range shoot was suprisingly good given the hardware.

It’s shocking how long it took the US military to get rid of the Springfield though.

Congratulations to Karl on his performance and Ian for putting this on the site.

“It’s shocking how long it took the US military to get rid of the Springfield though.”

Yes the Winchester lever-action has bigger rate-of-fire than single-shot Springfield, but the on the other hand is more complicated and therefore more sensitive to field condition and simply more expensive. So who have bigger rate-of-fire unit with Springfield or unit with Winchester but with price of all Springfields equal to price of all Winchesters?

Winchesters along with peabody martinis were used to good effect by the Ottoman forces at Plevna.

Ultimately the Ottomans lost the campaign, but made all militaries aware of the effectiveness of both of those rifles.

That the United State forces were still using trapdoor Springfields and having the Spanish American war in 1900, is a good illustration of why we all need central planners [not].

Was the rate of fire really that different? I remember seeing a demo where a trained guy fired 20 rounds in a minute from a Trapdoor carbine (not that I wish to do that to my shoulder). Seeing how long it took Karl to reload, his overall speed, other than the first 7 or so round burst, might not have been greater, and the 45-70 probably qualifies as a knock-down round even by the biggest magnum dude standards.

So we should consider two cases: long-time sustained fire and short-time fire squall. The Winchesters were used by Turks during Battle of Plevna with good results, but note that was on quite short distance.

–

Don’t forget that there were also Winchesters for bigger cartridge like Model 1876 chambered for .45-75 Winchester

Sorry Daweo – that’ll teach me to read all of the comments before jumping in.

“He isn’t shooting black powder, simply for ease of use (it was 105F during the match), but his .45 Colt ammo pretty much matches the ballistics of the original loads.”

Why there were not .45 Colt lever-action in these times, but they are now?

They did not chamber lever guns in 45 Colt originally because the rim size on the original balloon head 45 Colt cartridge was too diminutive for reliable extractor purchase.

The size of the rim on the 45 Colt cartridge was improved later in life thus making it viable for the Winchester or any other lever gun, for that matter.

I clicked post before I finished my thoughts.

There were also licensing issues; the 45 Colt was a proprietary and patented cartridge as well, meaning that there was little reason to try to license such a thing at the Winchester factory if you could just go with 44-40 (or other equally well performing cartridges).

“It’s shocking how long it took the US military to get rid of the Springfield though.”

U.S. Army Ordnance kept the Springfield in service because it was reliable with the poor ammunition of the day. The Winchester and other repeating rifles only slowly made inroads against the single shots as ammunition improved. Most ‘major caliber’ ammunition cases were fabricated by soldering copper strip around a wood mandrel into the 1880’s. It is only the introduction of the ‘Everlasting’ style case in the early 1880’s which allows the development of repeating rifles in serious cartridges.

44 Henry is frequently discounted as “not serious” but I’d argue that for its intended purpose, it was fine.

200 grains of FPRN lead ball at 1,200 FPS isn’t something I’d want to be shot at with.

It was the intermediate cartridge of its day.

In my opinion, the 1860 Henry and 1866 Winchester really were the AK47s of their time. They were not intended for precision or long range (although capable of hits and at least nuisance fire), but excellent for relatively close range combat.

Something not demonstrated in this match, because I went with convenience of smokeless, is the smoke cloud generated when firing.

When you let loose with 55 or 70 grains of blackpowder (45-55 or 45-70), you produce a significantly larger cloud than you do with 28 grains in the 44 Henry. Of course, as you rapid fire, that changes with the Henry cartridge.

We’ll do something with a Trapdoor carbine in the future.

Given the choice, I’d take a Henry or 66 any day, personally.

I wonder if a combination of the two types of rifles, a mix of Trapdoors and repeaters in the formations like the bolt action/smg equipped squads of WW2, would have made much of a difference in some engagements of the era. As for this particular battle, when one looks at the totality of circumstances (numbers, terrain, leadership, etc.) I doubt that had the 7th been equipped with M16s, as they were in the Ia Drang almost a century later, they would still have been wiped out.

It’s a curious idea and we’ll never know.

On the surface, I think that would have made a lot of sense.

The ballistics of the .44 Henry are quite close to the .44 Special and .45 ACP with a 200 gr bullet, so certainly it was powerful enough within its effective range.

An interesting theory that comes to my mind is that the longer variants of the 1866 with a 20 inch or longer barrel probably had a too long barrel for optimal muzzle velocity. I don’t know if anyone has made any muzzle velocity comparisons using period correct black powder loadings, but it would be interesting. What we do know is that back in the 1860s and 1870s there were no reliable methods of determining muzzle velocity and scientific understanding of internal ballistics was still very much in its infancy.

I haven’t performed such an experiment but I’d be surprised.

My experience with quite a bit of blackpowder shooting is that barrel length is more pertinent to velocity than with smokeless.

My guess would be that there would be an increase with the rifle versus the carbine. That’d be an interesting test to do in the future.

Sight radius alone would be beneficial for accurate fire, of course.

I don’t pretend to be an expert of ballistics, but the relatively small amount of powder in the .44 Henry cartridge combined with the fast burning of black powder might, it seems to me, produce a pressure curve similar to modern pistol cartridge powders. If that is true, it would mean that at the end of a long barrel the friction caused by rifling would exert a force greater than the gas expansion, which would decelerate the bullet somewhat. That is what happens with most modern pistol cartridges beyond about 18″ barrel length (in case of weak or lightly loaded cartridges even before that, but since no one would put a 20″ barrel on a .32 ACP gun, that is mostly academic). The deceleration would not be dramatic at first, however, so the difference between a 24″ and a 19″ barrel would probably be only few dozen fps.

My theory would definitely NOT apply to true rifle cartridges such as .45-70 or even caplock muzzle loaders, since they would have a much larger amount of powder. It would also not apply to any smoothbore black powder guns, since the friction of the barrel would be much smaller without rifling (assuming a reasonably clean barrel, of course).

There is simple method to measure bullet momentum – ballistic pendulum, but I don’t know when it was invented.

Note that in these times the rim-fire was considered as less reliable than center-fire cartridge.

The Spencer, already in inventory by the thousands in 1865, would have been a perfectly adequate rifle for everything the Army actually did between the Civil War and 1898. Probably up until 1917, too, although San Juan and Kettle Hills would have been a bit more difficult.

Unfortunately for the taxpayers the military still had to plan to be able to fight a conventional army, with its longer range capable Martini or Gras rifles. An important lesson of the first industrial wars was not to let your troops be armed in a way that let them be shot to pieces by longer range weapons.

I think George Custer would have lost if he had an atomic bomb and a jet plane!

It is interesting to note that the U.S.Army never adopted a lever action rifle.

All soldiers are not firing from a prone position!

That would have helped.

The levergun really isn’t that bad from prone, but definitely deficient compared to a repeating bolt gun.

While I didn’t fire anything from prone in this match, it’s still faster than reloading a Trapdoor.

Sounds like an interesting sub-topic video someday, Ian! 🙂

The U.S. Army adopt at least one and bought over 100,000 of them. The Spencer was lever action and it was replaced by the Trapdoor.

While the Spencer is technically a repeating lever gun, it’s nowhere near the speed of the Winchester action.

He did have both the Atomic bomb and the jet plane of the era, aka Gatling guns for area fire and sabres for a quick cavalry charge. He left both at home for mobility because he didn’t think he needed them against an inferior foe.

By doctrine he should have been able to defend massed around his guns, fight as light infantry in skirmish line, or conduct a massive charge into a densely packed enemy; he took two of the three options away before even going out to fight.

I have read that Custer was a Presidential hopeful in the centennial year (1876)!

Politics makes a mess of everything.

That is largely myth. There is no way the Democrats would have nominated an ex-general hated by the South. And after Audie’s contretemps with the Grant administration the GOP hated him at least as much

It was pretty much common practice in the Army then to leave Gatling guns and sabers home. In fact articles have been written arguing that everything Custer did that day way pretty much by the book. But, yeah. We’version all watched Little Big Man, so we have the inside dope

Hubris and incompetence are a deadly combination. I walked that battlefield about 20 years ago when I was working out west. Truly a haunting (and likely haunted if one believes in such things) place.

I think the Army also thought they preferred the long range characteristics of the .45-70 Trapdoor Infantry rifle.

I also think they took so long to replace the Springfield because they had, for many years, no real threat to give such a replacement any real momentum. Didn’t they run “trials” on a regular basis over the years and not feel the need to adopt any of the new designs?

The outcome of the Custer fight was more due to tactics than weapons. Custer divided his force in the face of a numerically superior enemy and worst of all, attacked in late afternoon, which is the middle of the day for Indians, when the whole camp is awake and active. You would think that a supposedly experienced Indian fighter like Custer would know that…

Terrain more than tactics.

The tactics he used were not unusual to many other successful attacks previously (and subsequently) realized.

When your rifle is specifically designed to keep the enemy at range and they are able to out maneuver or over-run you to close beyond that range, that’s when the trouble begins.

This occurred for more than these reasons, but I think these two in particular:

1) Numerical superiority; they literally we overrun.

2) Knowledge of terrain and movement. The natives knew the landscape and the terrain and were able to maneuver undetected to subsequently suddenly appear well within the range of their weapons. You then get your one 45-55 shot off and fumble to reload as the fusilade of fire is inbound.

The archaeological studies have shown that Custer’s troops broke up into small groups which were easily overrun. The same disintegration happened to British forces at Isandhlwana with the same disastrous outcome. At Rourke’s Drift a much smaller British force maintained its integrity and fended off the same Zulu’s who were victorious at Isandhlwana.

The U.S. Civil War greatly affected the thinking of U.S. Army officers who participated in it. To a man they preferred long range riflery to the close quarter butchery which characterized many Civil War engagements. This was a driving force behind the establishment of the National Rifle Association and the various Boards for the Promotion of [Civilian] Rifle Practice. No way would Civil War veterans have accepted an intermediate cartridge.

What I have to remember always is that I never lived in the days of horses. Everything I know about is or was transported by coal, oil, or maybe nuclear fuel. If a grunt has to carry a hundred rounds that won’t be fired in excess of a football field, why wouldn’t they make the cartridges smaller?

I believe that much of the expedition’s supplies (remember that the battle was a part of a 3-pronged offensive directed against Sitting Bull: Gen. Crook from the south, Col. Custer from the east and Col. Gibbon/Gen. Terry from the west) were transported by shallow-draft steamboat, the Far West, from the Yellowstone up to the Bighorn river not far from the battlefield, so logistics wasn’t as big of a problem as is often assumed. The problem was the perceived “need for speed” when pursuing native war parties who were once described by a contemporary author as “the finest light cavalry in the world.” Thus, anything deemed too heavy (Gatling guns, 12 pounders, sabers, etc.) was available but left behind in the interest of rapid mobility. The Trapdoor carbine fired a reduced charge (55 grains of BP vs. 70 grains in the infantry load) but in a similar length case, thus there would have been some minor weight savings. I know that when Marlin came out with a lever-action 45-70 repeater in 1881, many officers serving in the West purchased them for personal use, giving them, in some ways, the best of both worlds.

At Islandwahna archeologists found the British troops were initially deployed too far out from the main camp (some 300 yards) and were too spread out for effective mutual support; analysis also showed that the Martini Henry’s fouled rapidly resulting in cartridges becoming increasingly hard to extract, this meant rates of fire dropped off rapidly. Many of cartridges were also found with torn bases due fouling at which point the rifles became second rate clubs and pikes until they could be cleaned. Ultimately this resulted in the troops being overrun abd massacred. It also didn’t help the quartermaster was an idiot and would not allow “HIS” ammo to be distributed in bulk but only in limited quantities…and the commander was a fool.

Didn’t Quantrill show that multiple revolvers were pretty effective? Two .36 calibre revolvers for close in and the Springfield for distance might have been a good combo.

We have to remember that cartridge ballstics up until about 1900 (say 1906 for the US Army) were driven by the need to stop a horse at considerable range – not a man. The cartridges of the day were over-kill for a man. Stopping a cavalry charge was the driving design criteria (ever wonder why all the world’s military’s were still chambering 200+ grain bullets in .30 cal-ish cartridges?). Of course, the Indians didn’t care. They used what was available. They understood the firepower vs long range accuracy trade better than US Army Ordnance did.

Army Ordnance always seems to be behind the times! They decried the whole repeating rifle concept as being wasteful of ammunition, dismissed the Maxim and Colt/Browning machine guns in the 1890s as being “no better than the Gatling,” and when they finally did decide to go with a bolt-action repeater, they selected the inferior Krag-Jorgensen (and lets not forget the whole Lewis Gun fiasco in WW1). Hell, my 03A3 still has a magazine cutoff so it could be used as a single shot rifle in 1944! It would be funny if it hadn’t gotten good men killed for lack of proper equipment.

It seems that Ordnance can work mainly in 2 ways

We’re glad with our current guns and we don’t want anything new XOR We desperately need new weapons to avoid being overguned by enemy.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Springfield_Model_1892-99 states that “Despite protests from domestic inventors and arms manufacturers — two designers, Russell and Livermore, even sued the U.S. government over the choice — the Krag-Jørgensen design was chosen by the board of officers.” so this is apparently is 2nd case: fast not necessarily fair

True. I’ll take issue with you on the Krag. At the time it was adopted, nobody yet knew what the superior bolt action magazine rifle would be. The Krag wasn’t a bad rifle. It was accurate and reliable (read Shockley’s book). I do wonder if there were kickbacks involved when it was picked during the original trials though. There is no documented evidence to this, but Flagler surely showed favoritism. The Ordnance dept overplayed the significance of being able to top off the magazine with the bolt closed (one of the primary reasons stated for choosing the Krag). Also, why they didn’t choose the Krag design with the dual locking lugs (one exists in the Springfield Armory Museum) is beyond me – unless it had to do with Springfield Armory’s obsession with interchangability and desire not to hand fit each bolt. Maybe Ordnance couldn’t foresee the need for a receiver that would hold more than 40KSI chamber pressure. I will agree with your overall statement though – Ordnance was very set in their ways and typically behind the times. Its amazing the M1 Garand ever came to be and even it was over-engineered.

Now you can say that the pressure generated by cartridges will rise and “receiver that would hold more than 40KSI chamber pressure” will be required but then it was not certain, so they were not eager to implement the feature making gun more expansive which may or may not be used in future. Decision like this was done not only in US Army, the German Empire Army ends with 7.92mm cartridge with Spitzer bullet and 7.92mm cartridge with round-nose bullet which has other bullets diameters and therefore were not interchangeable, Russian Army adopted Nagant 1895 using gas-seal which makes this revolver more complicated and providing neglible increase of muzzle velocity.

Back on topic – I believe Custer got his men killed because he was foolish, egotistical, under-rated his enemy and employed foolish tactics. It wasn’t because he was poorly armed.

Agreed. His ego wrote a check that he (and his men) couldn’t cash. That’s not to belittle their courage. Custer’s brother, Thomas, was a double Medal of Honor winner. George was jealous of Tom’s “little baubles” as he called them, and seemed determined to prove himself at the expense of his subordinates. Of all of the history I’ve read on the Indian Wars, I still find the most accurate (at least in my twisted mind) portrayal of Custer’s personality is Richard Mulligan’s role in “Little Big Man.” We know that his widow, Libby, actively promoted the “Custer Myth,” but it seems, at least from my reading, that his subordinates, particularly Benteen and Reno, despised him. Some suggest that Benteen deliberately ignored Custer’s order to advance in order to see him humiliated. (BTW, I think the Krag is a decent rifle with a beautifully smooth action, but I’m a bit of a Mauser fan.)

Surprised no one’s brought up the Battle of Beecher’s Island in 1868, where a unit of 50 cavalry scouts armed with Spencers held off a band of Indians estimated at somewhere between 200 and 1,000 (apparently they were too busy for an accurate count) for three days. Besides the Spencers, they had some advantages over Custer. The unit was handpicked from experienced scouts by its commander, Major Forsyth. They were able to take up a good defensive position on a sand bar where they dug in or killed their horses to use as breastworks, while the Indians had to charge across the open riverbed to get at them. Still, one has to wonder how well they would have done meeting the charges if armed with trapdoors.

I stumbled on a very interesting article by Charles King (Captain, 5th Cav) from 1880 in which he addresses the then-popular opinion that the Trapdoor was obsolete and largely responsible for the Army’s various defeats. He suggests that instead, the Indian tactics were so far superior to the Army’s that the best rifle in the world wouldn’t change the situation materially for the Army. It’s titled “Arms or Tactics?”, and I’m looking for a copy online so I don’t have to transcribe the whole thing…

An interesting parallel to the Battle of the Little Bighorn took place nearly ten years earlier near Fort Phil Kearney and is known as the Fetterman Massacre. Poor tactics and disrespect for the natives’ fighting ability were the primary contributors to the annihilation of both infantry and cavalry in that engagement. The regular troops were armed primarily with muzzleloaders. According to the after-action reports, the majority of the native casualties were inflicted by two civilian volunteers (James Wheatley and Isaac Fisher) who were armed with Henry repeaters. Although Fetterman was a decorated Civil War veteran, he was completely outsmarted by the natives’ tactical skill in their own brand of warfare, so there is much to be said for that argument. However, the deadly efficiency of the two Henry rifles suggests that repeating rifles in general issue could have made some difference in certain engagements, so I’d say the fault lies with a deficiency in both tactics and weapons.

Back to the match – the shooting out the car windows struck me as a pretty good proxy for various difficult close-range circumstances (off of or behind a horse, reaching around a rock, etc)

And it would seem in those conditions, with a little luck about when to load, the lever rifle would have had a big advantage.

[But I’ve never shot a trapdoor and have only a readers idea of how they work.]

Actually, a great comparison might be trapdoor versus lever….

If you’ve ever ridden a 19th century cavalry saddle or gone horseback for miles on a 90 degree High Plains day…it gives you a whole new appreciation for a soldier’s life in those days.

Another factor to consider: conventional cavalry tactics of the day called for every fourth man to “hold the horses” (must have been fun trying to control four of those old jug heads at once, huh?) so as soon as you dismount the unit and form a skirmish line, you’re down to 75% effectives.

Of course we don’t know for sure if Custer even got that far. It looks like the command basically fell apart under the force of the overwhelming numbers pouring out of the coulees at relatively close range.