The Remington Model 8 (and the 81, which is mechanically identical) was an early self-loading rifle design by John Browning, and was produced from 1906 into the 1950s. It was available in 4 calibers initially, all of them being rimless, bottlenecked proprietary jobs – the .25, .30, .32, and .35 Remington. The .35 was the most effective on game and was the most popular seller, with the .25 being the lest popular. When the Model 81 was introduced (with a heavier forestock and semi pistol grip), it was also made available in .300 Savage. At that time, the Remington factory also offered to rebarrel existing Model 8s for the .300 Savage.

The Model 8 was a long-recoil design, something that saw little further development and remains one of the least-common types of action. It is interesting to compare the Remington 8 to the Winchester 1905/07/10 series of rifles that came on the market at almost the exact same time. Both were well-made and effective self-loaders, but with much different target markets and mechanical systems. Winchester opted to make a replacement for the pistol-caliber lever action saddle rifle, and did so using a simply and somewhat brute-force operating system: direct blowback with a heavy bolt and recoil spring. Remington, on the other hand, wanted to make a big-game rifle with very fast follow-up shot capability, and used the far more complex long recoil locked breech system. Both guns are largely forgotten by the gun-owning public today, although they both were widely used and appreciated by hunters for decades.

Anyway, I had a chance to do some disassembly and shooting with a .25 Remington Model 8, and recorded the process on video:

I should also mention that I have a .300 Savage Model 8 in my personal collection, and will be using it to shoot one of the local 2-gun action matches in the next few months…

Ian, Remington 8 was used in Russia during WW1, I have seen photo of Caucasus front in 1915, 3 soldiers in shallow trench one reloading Model 8 by stripper clips (judging by size of round .35 is my guess), two holding them. I am leaning toward theory those were privately acquired rifles, as a lot of sporting rifles saw use in 1915 – I have seen pics of scoped Winchester single shot (model 1886?) for sure.

Sorry, Model 1885 single-shot.

that is the best design of a rifle I have ever saw I would take that old rem 25 over a new colt m4 anyday

the hi speed video of the long-recoil is really cool

and i thought that it was kind of funny how that the ejected casings bumped into Ian’s head

Ian –

I would be interested in your perception of felt recoil in the Remington 8/81. Despite being heavier, the Remington automatics always seem to me to have more recoil than Remington 14/141s, Savage 99s and Marlin 336s in the same cartridges.

Can’t imagine firing one of the full auto law enforcement Model 8s with the PECO 15 round magazines.

note:

Remington 8 = straight stock

Remington 14 & 141, Savage 99, Marlin 336 = pistol grip stock

I wonder: is it only coincidence or rule applicable for any firearm? This rule can be described “pistol-grip = significant less felt recoil”. Additionally note that Winchester Model 71 (firing powerful .348 Winchester round) also have pistol-grip.

Oh yes, a .30-30 Winchester 94 with a straight stock is absolutely brutal to put 20 or 30 rounds through compared to a pistol-grip Marlin 336. There have been several sweet-handling light-weight straight-stock carbines (with metal buttplates, more often than not) that I have passed on because the obvious physics of the situation were obvious. The (late, great) Ruger #3 carbine in .45-70 as an example… great little rifle but while I was holding and drooling over one I ran the math and said “This thing kicks like a mule.”

That complicated modern rifle certainly grabbed my attention; thanks 🙂

thinking about the reputation for heavy recoil; I suspect that the long recoil operation requires the barrel and action to hit the stop at the back of the receiver with a healthy amount of momentum remaining, in order to ensure reliable operation if its dirty, cold, lacking lube etc

allowing a longer travel would result in a longer heavier receiver, and result in the mechanism which catches the bolt to unlock it, receiving more of a battering, as the bolt would have had time and space to reach a higher speed.

short of somehow smuggling a stack of bellville washers in there as a buffer (who’d want to do that to such a cool old gun?), it looks like the reputed sharp recoil of the .350 is an inevitable feature of putting a large round into that design.

“http://thegreatmodel8.remingtonsociety.com/?page_id*1562” has detailed info.

Thanks for the video.

Damn buy yourself a set of good hollow ground screwdrivers so you have less of a chance to bugger up gun screws.

*scuffs dirt with toe* Yeah, I know.

Yup, definitely not your 10-second field strip gun… It’s much worse to field strip even than the BAR. Browning might have been a genius, but sometimes the mind of geniuses take kinky paths, indeed.

And talking of inspirations from Remington 8 – AK and FAL, you’re right, but what about the Johnson 1941 rifle and LMG and the bolt handle?

Model 8 DNA found its way into all sorts of places. The garand (and AK) bolt carrier and locking cam arrangement strikes me as an improvement though, especially after the M14 roller was added to the bolt.

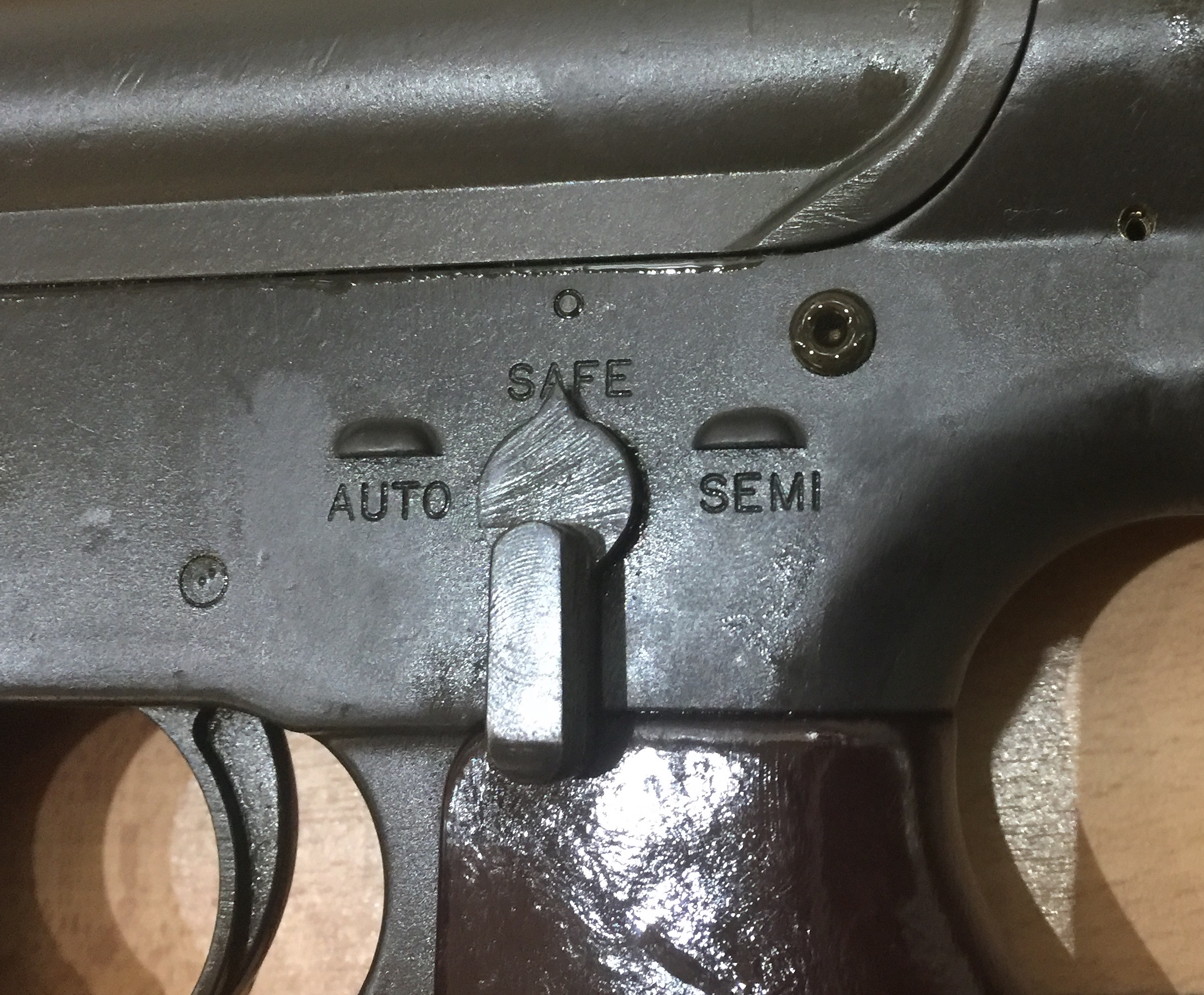

That safety arrangement looks reminiscent of the Ak, actually if you put the barrel on top of the bolt, that reminds me of a Ak, it is quite likely Kalashnikov saw one.

The French RSC Mle 1917 is another distinctly Model 8-like design. Check out this photo of the trigger group: http://s1143.photobucket.com/user/MountainPrepper/media/Camping/Firearms%20Parts/RSCMle1917TriggerGroup.jpg.html

The article it came from:http://mountainpreparedness.blogspot.fr/2011/04/french-connection-in-history-of-m1.html

While I am waiting for my previous comment to be reviewed, I think the designers of the RSC, Ribeyrolles, Sutter, and Chauchat, and John Garand were both looking at the Model 8 when designing their respective weapons, the difference being in using gas rather than a recoiling barrel for the motive power.

Has Ian just been volunteered into doing a disassembly vid of a Chauchat?

I have a friend in the process of re-watting a Chauchat, and I have been looking forward to doing a disassembly and shooting video with it for quite some time!

I was talking about the RSC Mle 1917, not the CSRG. Though, your suggestion is a good one.

Long recoil turned out to be a dead end in arms development, though I like my Browning Auto-5. It too is a Chinese puzzle inside. As already remarked above, Browning is credited as a genius, but sometimes his reasoning is hard to follow.

Something I have read–not sure that it’s true but it sounds likely–is that Browning relied on the original version of 3D modeling, grinding and shaping and fitting together actual parts until he made something that worked. When finally it did, it no doubt made sense to him.

Browning was genius inventor but generally poor engineer. Most of his designs had to be fine-tuned to enable mass-production.

This can be applied to almost any factory-made early 20 century automatic or semiautomatic rifle (excluding the designs for less powerful round, for example Winchester Model 1905) – see for example: Mondragón rifle, Meunier rifle, Sjögren shotgun (yes, actually it is not rifle), Fedorov Avtomat

John Garand was rather an exception, in that he designed the guns, and all of the production machinery to make them. Of course, other engineers from time to time improved his processes.

It seems to me like the long recoil action, like with the Danish Bang system (another dead-end), was just another way firearms engineers tried to get around having to drill a hole in the barrel required for the proper gas piston system that, as we know, is dominant today. I still have a hard time understanding why designers of many early autoloading rifles seemed so deathly afraid of the concept of putting a small hole in the barrel for such a long time.

I suspect they avoid hole in barrel because:

1.they think that it will make barrel weaker and hence it will blow

2.exist many black-powder cartridges from which smokeless variants were derived, hence the black-powder round can be loaded to gun designed for smokeless ONLY and jamming the gun (note: the Winchester Model 1903 use their own unique round – .22 Winchester Automatic to avoid loading black-powder .22 rim-fire cartridges)

The Maxim guns barrel, is sort of long recoil, and given that was kind of the start of automated weapon functioning, perhaps alot of early designs went along those lines.

The Maxim is a short-recoil design, the difference being that the distance the barrel recoils back is less than the OAL of the cartridge (a lot less).

Oh right, still, barrel moving attached to bolt… Might have focused folks minds, thinking along those lines.

Would black powder not work then with “hole in the barrel” gas port, designs… Is that because of fouling, or wouldn’t it work at all? Is smoke not “gas” so to speak.

Chinn discusses the mechanical reasoning (as opposed to fouling, cleaning and corrosion reasons) against gas operation in volume 4 of “The Machinegun” (scroll down here for a free .pdf of it http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/MG/ )

Ideally, to avoid chipping, burring and otherwise distorting and destroying the rifling lands (and accuracy), the hole should be drilled through one of the grooves ( these are typically twice as wide as the lands ).

That sounds relatively simple, just index the barrel blank for one of the grooves at the end, and calculate how far allong it to drill to hit the centre of a groove…

after that comes the difficult part!

If the barrel is to be threaded in, the threading needs to be indexed correctly to bring the barrel sufficeintly tight and with the gas port hole correctly timed to line up with the gas block

This of course precludes using the screw thread to adjust for head space.

Chinn points out that in cannon, gas operation normally requires greased cases, due to poor control of head space – the grease allows the case to move back rather than separate under conditions of excess headspace.

Simply put, gas operation (if you want to engineer it correctly) introduces a lot of engineering headaches. If you bodge it, for example by hitting a rifling land or even worse, the edge of a land, and form a cutting edge, you will get even more headaches.

Well that sounds complex Keith, there was something to the Bang type principle in regards that.

J. M. Browning never learned how to create engineering drawings. He cut cardboard sections of his parts to scale, stacked them up to make ‘parts’, and passed these ‘parts’ off to his brother who converted them into engineering drawings. Browning probably suffered from autism, but this was the root of his mechanical genius.

Browning was the first to develop gas actuation in firearms, but had terrible problems with the dirty burning ammunition of his day. This is why his Model 1900 shotgun was long recoil. Black powder shotshells predominated into the 1920s and long recoil was the only automatic mechanism which could cycle BP loads reliability for many hundreds of rounds. The friction ring system of the Model 1900 shotgun was a stroke of genius, without which the design would have failed to handle the range of shotshell loads then sold.

FNH was so happy with the sales of the Model 1900, they asked Browning to adapt the design to rifle cartridges with as few changes as possible. They wanted it to share as much as possible to ‘bask in the glow’ of the Model 1900 shotgun. This was the FN Model 1905 rifle, which is what the Europeans used in WW I. The Remington Model 8 launched a few months later.

In the 1890s also von Odkolek patent the gas-operated principle, later his patent was used to design Hotchkiss 1900 MG.

–

“J. M. Browning never learned how to create engineering drawings.”

Note that Margolin (Russian: Михаил Владимирович Марголин) the designer of MCM pistol (also named simply Margolin pistol*) also don’t use any drawings, because he was blind (due to head wound in 1924) and therefore he use the plasticine, wax e.t.c. materials when he designed firearms.

*nowadays only the MCM pistol and their derivatives are popular, but Margolin craft also another firearms for example see ТКБ-205:

http://www.pistoletik.net/tkb-205.html

It was tested in 1940 as a sidearm for Red Army, it was close to adapt but the new requirement was added: the DA trigger. It was not done until the war broke out and later this project was canceled. Cartridge: ПП-39 (similar to 9×18 Makarov), action: blow-back, quantity of parts: 23 (defined as a “factory parts”)

If a model 8 is to be in a two gun match, do a Bonnie and Cylde theme (Model 8’s were used by the Texas Rangers in the ambush). A Model 8 and a 38 super 1911 vs a BAR and a Colt hammerless 32.

Oh, and you would have to have someone with a 1907 Winchester .351 Winchester and a 3 1/2″ adjustable-sight N-frame Smith .357. (Or a Military and Police .38/44, if you want to get totally Stephen Hunter about things!) And make it a 3- gun with a real (not NORINCO) Winchester 97 12-guage with the ventilated handguard and mount for a Springfield bayonet.

With .351, you would be into .357 max territory with ballistics, and unless you have a long enough cylinder, you’d probably also have the same forcing cone and gas cutting issues that plagued the .357Max in revolvers.

I forgot to add, the .351 case was semi rimmed so it would likely have worked as a (highly impractical) revolver round.

I’ve always wondered how the .351 would have worked in a long-frame Smith N with half-moon clips. I’ve had both Colt and Smith 1917s and I will take a pocket full of half-moons over a pouch of speedloaders any day. Just really odd that for a round that stayed in gun production for a half-century (I think the 1907 was made until 1958)I don’t think any other gun was ever chambered for the .351. Would have been interesting in a light bolt carbine or a single-action revolver… the DA with clips is a fun concept but I would bet on sticky ejection even if Smith had made something (odd bore and cylinder length)so unusual.

Hi Jim,

If you are interested in having a play with that concept, check out Barnes’ Cartridges of the World, 6th edition.

There’s a guest section at the back by Elgin Gates, he covers his .357 “super mag” from page 398.

the right hand column on page 399 discusses Gates’ thoughts on the minimum cylinder length necessary to avoid gas cutting a forcing cone erosion problems.

In revolver cannon practice, the barrels were rifled with a gain twist to reduce stripping of the bullet and rifling in the forcing cone (probably over kill in a .35″ cal revolver!)

It seems that Dan Wesson built revolvers with the 2.075″ cylinder length which Gates recommended. They also have easily changed barrels. A good thick layer of hard chrome into the chambers and honed / lapped (line bored with home made diamond tool if you want to be a real perfectionist) out to the appropriate dimensions, coupled with a new extractor star and an epoxied in shim to adjust head space, would probably allow the factory cylinder to be used with .351.

The commercial Rem .357 max had a case length of 1.59″ that of the .351 is 1.380″.

case diameter of .357 mag / max is only .002″ larger than .351, so a simple full length size will easily reduce max brass to the correct diameter, the rim needs 0.010″ taking from the front, and 0.030 from its diameter.

Alternatively, for anyone who has the inclination and access to a turret lathe or a screw machine, sleeves with the appropriate rim dimensions could probably be made up to force fit onto cut off .223 brass.

I do not have any not have any forcing cone or gas cutting problems with the .357 Max in my Thompson Contender. Wonderfully accurate, also.

Steve

Indeed – .357 Max showed the limits of performance in .357″ revolvers with standard length cylinders.

I dread to think what the service life is for the .223 revolvers made in the backstreet shops in the Philippines.

Go for 3 gun and use a Remington Model 11 too!

Î This! [Plz!]

Fiddly dis-assembly turns off the army! No wonder it doesn’t make a good choice for the trenches. Too many moving parts for the dough boys to handle means that this gun would probably have ended up like the Mauser self-loader carbine. Both guns were complex, expensive, and both did not like mud.

Ian,

It almost looks like you could take the barrel assembly and bolt from a Model 8 in .35 Remington and install it on the .25 Remington rifle (and have it fire .35 Remington!).

Thoughts?

Steve

I haven’t tried, but I think you probably could. The casehead dimensions were all the same, so one bolt should fit any of the cartridges. Not sure if a random new barrel assembly would headspace correctly, though.

You can interchange barrels on .25, .30, and .32 Remington calibers with no further alteraqtions, except the .25 Remington recoil spring is uniquely limp. A lot of the .25 Remington Model 8s got rebarreled due to the effect of corrosive ammunition and poor ammunition availability. .35 Remington is a larger case and requires a magazine change, bolt change, recoil spring change, and opening the receiver charger slot. .300 Savage also has a unique bolt, spring, and magazine, and requires a yet wider charger slot as well (to use M14 chargers). Bolt headspace was interchangeable within caliber families.

Note that cartridge common-dimensions-crucial-for-cycling is also present in Winchester cartridges for Model 1894 – .38-55 Winchester, .30-30 Winchester and .25-35 Winchester have equal: rim diameter (.506) and base diameter (.421 is noted for .38-55 and .422 for two others – the difference is only .001 and it is probably simple factory tolerance) and rim thickness (.063*).

(source: articles about cartridges in English wikipedia – excluding * which is from http://www.loaddata.com/members/search_detail.cfm?MetallicID=2161)

Can be Model 94 simply converted between any of this cartridges by changing the barrel or others alterations must be done?

A sort of “modular” design, like having the same calibre barrel but with different length cartridges, to use the same bolt. But this has different calibres, with the same bolt presumably. Might be a better way of doing it, 7.62x39mm cases can be made into 9.3mm calibre ones apparently, and these two calibres act differently to one another i.e. the bullets, rather than the length of case available sort of thing.

Take a look at the newish Merkel Helix straight-pull. Austrian and pricey but a really neat design. Comes in three different action sized (small .222/ 223, standard rounds, and belted magnums) but the barrel/chamber pops right off for changing. I would love to have one in a 6.5 x 55 and 9.3 x 62 on the standard action (that would cover everything I am interested in shooting and eating) but then I would have to buy a wood shop to build the velvet-lined mahogany carry case….

Worth mentioning that the .30 (and .25 and .32) Remington was the basis for the 6.8 Remington SPC, which was the only thing that has really intrigued me about black rifles in years. Neat cartridge, although it doesn’t seem to have caught on.

The Remington 8 and 81 were… no other word describes… elegant. Can’t say I’ve ever had the clerk in a gun shop hand me a more elegant semi-auto rifle. Just out of curiosity… I would swear that at some point I saw a reprint on a 1920s European gun catalog that featured the FN version of the Model 8 in a “9 x 57 mm.” Was the FN-8 (or whatever they called it) really made in 9 x 57 Mauser or was this a translation of “.35 Remington”?

In Europe, the .35 Remington was known as the 9x49mm. I would guess the listing was for a 9x57mm Mauser chambering.

The .30 Remington is also the parent case for 10mm Auto, which itself is a parent a case for .40S&W, so nowadays the daughter cartridges of .30 Remington are more popular than the .30 Remington itself.

source:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/10mm_Auto citing “The Handloader’s Manual of Cartridge Conversions. Stoeger Publishing” and “Designing and Forming Custom Cartridges. Precision Shooting.”

Here’s a link to a pretty decent Model 8/81 site:

http://thegreatmodel8.remingtonsociety.com/

I’ve never made a real search for one and have only run across a couple of them. I sure like like to try one.

After seeing this video, I’m glad that when studying one years ago my desire to avoid problems out weighed my curiosity after I removed the barrel.

I’ve read that Fedorov said that the .25 Remington was the perfect military round and there was no need to look a anything else.

He did and he was right? Or at least closer than anybody else back then. Just IMHO! But if you want to think a bit harder on it, the 6 MM/ .236 Lee Navy was a better cartridge. All it needed was spire point bullets. The exact same thing as the .25 Remington round! I wonder why no one thought to carry them over from the old lead bullet days in the 1830’s?

But now new question: when the Fedorov say this?

It is obvious that during the whole handheld firearms development history the bore diameter shrunk – later firearms have smaller bore diameter. The question is: it is the minimal limit for this rule? or the point when bullets are too small (light)? I think yes. The .223 Remington is too small as a military round (i.e. with no expansive bullet – no hollow-point and no dum-dum). I think that the .257 (also named .256 or .258) or .264 is ultimate military rifle cartridge, but the bullet weight and velocity can be discussed. After-mentioned cartridge have good reputation as a hunting cartridges: 6.5×54mm Mannlicher-Schönauer (.264), 6.5×55mm Swedish (.264), .257 Roberts, .250-3000 Savage (.258). Note that also during trials of cartridges for Pedersen semiauto rifle:

“The Board found all three rounds (.256, .276, and .30) were lethal out to 1,200 yards (1100m), and wounding ability out to 300 or 400 yards (270-365m) was comparable. The “tiny” .256 caliber round was perceived to be the deadliest of them all. No compelling case could be made against the Pedersen rifle and round that it could not perform on the battlefield.”

from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedersen_rifle

The .280 British sounds like a decent round also, there’s these new 6.8mm ones as well, .243 might be ok, that 5.8×42mm Chinese case sounds good, case width is quite important though isn’t it to avoid overly large magazines.

With small caliber rounds, you need speed. Kinetic energy is K.E.= 0.5*m*v^2. That’s only for a non-rotating body, after which one adds angular terms. Then our equation is:

K.E.= (m*v^2+I*w^2)/2, where m is mass, v is linear velocity, I is the moment of inertia of our projectile normal to its ballistic trajectory, and w is the angular velocity measured in radians per second. With all of this in mind, the small caliber round has little mass and a small moment of inertia. But if v and w are large, say supersonic linear speed and good rifling twist rate induced rotation, then we’ve got a nasty little surprise for the idiot using an SUV to hide from a Type 38 Arisaka or an old 1891 Carcano long rifle 100 meters away. Didn’t we post concerning Remington Model 8 ammo testing last year?

There’s a small point which you omitted; The military service 6.5mm rounds used bullets in the same weight range (140 to 160 grains) as the .30-06 and the 7.62x51mm, but at slightly lower velocities, due to the smaller basal area of the bullet and lower operating pressures compared to those .30 cal rounds.

It is little surprise that similar weight bullets delivered at similar velocity had similar terminal ballistic performance.

6mm SAW sounds good, all round.

He said that between the wars, IIRC? (If not, it was before WW-I!) But the 6 MM Lee Navy precedes the .25 Remington. The Lee could launch 75 grain, or about 5 Gram bullets at over 1,000 M/S! Something I find most desirable! Hi-velocity confers flat trajectory and short time of flight, both very important qualities for making an “Effective” weapon. You have to remember that something more than 90% of all infantry battles are at ranges less than 300 meters! Also that recoil and muzzle blast are detriments to combat accuracy. All of these facts point toward smaller caliber ammo.

The smallest practical ammo must be large enough so that “capillary filling” does not retain, or induce water to enter or stay in the barrel. Thus the lowest possible edge of the curve is about .17 caliber! Smaller than this, while eminently practical and desirable from so many other points of view, is eliminated from all consideration. When one then looks at the energy required to produce a Militarily useful wound means that the smallest weight of bullet is about 2.5 grains, IF it has enough velocity! When energy at range is added to the question, then the smallest effective bullet weighs about 25 grains, if it is very pointed and has a significant boat tail! We know from millions of handgun wounds that larger caliber and heavier bullets do not confer any advantage that is commensurate with their increased weight and logistics load.

Thus we are left with the last two or three decades worth of micro-caliber ammo like the G-11’s caseless ammo, the Royal, or is it British Army’s 4.85X49 round and many other serious tries at new and ever more effective ammunition!

The last thing to think about is that Armies buy for the average conscript, not for the 1%ers who can shoot and handle the recoil of more powerful ammo. Therefore, only calibers that maximize effectiveness out to 3-400 meters and lessen the Log load will be adopted. There is nothing wrong with 5.56X45 that a little education would not fix! And certainly nothing wrong with even smaller calibers because it is not the caliber of missile, but the motivation of the target and exact location of the hit that is important. A good hit is always 100% effective and a bad hit is variable regardless of caliber. Given the statistics of combat, there will be very many more bad hits than good and anything that helps us get more hits is better than anything that reduces the chances to get both multiple and better hits is bad. Thus the smaller the caliber, the better!

I own a first year production Remington Autoloading Rifle (as the Model 8 was known before 1911), in .35 Remington. Quite a pleasure to shoot. It has the hand-engraved caliber on the receiver ring and early-style safety lever. I got it from an old-timer who bought it in upstate NY in the 1960’s.

I am very pleased to see you feature this firearm here – I am a longtime fan of your website. I am doubly pleased to have this video as a resource for the basic disassembly of my rifle. Thanks!

There is an interesting “Delayed Blowback” adaptation patent for this rifle

belonged Fraanklin K. Young with Serial No: US0998867 published at July 25, 1911.

Appearently it uses a similar construction with Pedersen’s “Hesitating Lock” and

patent text uses “Main Spring” term as “Recoil” or “Return Spring”.

Great gun to do a video feature on!! The slow motion video of the long recoil is fantastic! In many ways this rifle is somewhat forgotten. You see them occasionally at shows and auctions but I think most people overlook or simply don’t understand how significant the rifle is with respect to firearms design.

There is a good book on the Remington model 8’s and 81’s that is available from Collector Grade Publications. We’ll worth picking up. It covers the rifle’s history- sporting, military, and police use.

Thanks for a great post Ian!

https://www.forgottenweapons.com/book-review-the-great-remington-8/

🙂

Hi!!!

I loved watching your video, its nice to see your interest in such a historical rifle. I grew up in the great state of Maine and have seen first hand what these rifles can do. My wife’s farther had a Model 81 300 Sav. and I know of quite a few old timers with Model 8s. These rifles were used extensively for hunting large game and supporting the woodsman’s family. I remember many old stories of deer, bear and moose and have shoot a few myself. I have two Remington s, one Model 8 (1916) in 32 Rem, I lath 30 30 Win. shells and resize them to 32 Rem. which works perfect for me. I have a model 81 (1946)in 300 Sav. in factory left hand, and both are in excellent condition. These rifles and calibers are the finest shooters of the deep woods money can buy. I approaching my old age now but will grab for the Remington every time I go hunting. The Model 8 is lighter and handles very fast, makes up the difference when I need to follow fast moving game.

I watched you follow through positions, running, reloading time & accuracy in your video, you never missed even with a hot barrel. You look like you belong in the deep Maine woods to me.

Arthur Michaud

I was privileged a few decades ago to find an old Model 81 Deluxe (Williams peep sight version) in .35 Remington, with a broken firing pin (and original owners manual (guide)) sitting in a pawn shop forlorn, lonely and ignored and unwanted by any of the buyers all gung ho about newer toys with no broken parts. The purchase price was $90 which I happily paid, went to Brownells and found a new firing pin for it and dropped it in.

Your field strip video is needlessly complex for most purposes. After removing the forend and the barrel, pull back on the bolt till it locks, grasp that little pin on the bolt handle (with practice you can do it with your thumb and index finger nails with no needle nose pliers needed), raise it and slide the bolt handle off. Now, catching it as it goes forward, hit the bolt release. Voila, bolt is removed for cleaning. Further inside cleaning can be accomplished with some Hoppes, a long stemmed wooden Q tip type implements and a pen light. There exists zero need to fiddle about with slotted screws, remove the stock or drive out any pins whatsoever for most simple cleaning purposes. Reassemble in reverse order.

Use in hunting. Careful period reading shows most did not like the 165 grain bullet for deer in the woods. Too often it deflects or simply breaks apart on unseen twigs between you and Bambi. The 200 grain is more resistant to that phenomena. Once my new firing pin was installed and I zeroed out the sights to be dead on @ 100 yards with the 200 gr. load I couldn’t wait to try it out.

Observations. The barrel is too long for easy woods use. It may be just fine on a mountain trail with no brush and a grizzly bear coming at you (love that old poster, but I think I would want a much bigger gun for that bear, maybe a portable 37mm anti tank rifle with explosive shells, not a little .35 Rem), but in thick brush the barrel often snags when swung up quickly. Also it makes the gun needlessly heavy. I understand there is a gunsmith offering to replace the long barrel with a carbine length barrel (and a heavier barrel spring), but I haven’t done that yet. My front sight is brass. I don’t like that on sunny days or sunrise/sundown. In civil twilight (15 min after sundown) my front sight virtually vanishes. If I get the carbine barrel, I will also have him put a hi viz flourescent sight, maybe green or orange. I don’t use my 81 much because I found out the 200 gr. load, while great for brush busting, also as currently made with thick jackets, tends to greatly over penetrate my deer with much energy wasted on the woods behind the deer. So maybe once every 3 or 5 years I take it from the safe, but otherwise use something less wasteful of muzzle energy. Nonetheless, it is a great gun and I do wish to try one of the aftermarket carbine models and maybe do so to my own.

Noting with bemusement Remington (in emails) is less than friendly or enthusiastic to emailed questions about the M-8 and 81, serial number years, shipping data, etc. saying only these are obsolete designs and one should look at the newer models. 🙂 Shame on them. I wonder what that design would be like with a lighter stock, a carbine barrel, and an aluminum receiver…

BTW, Hatcher in his Handbook mentions these long recoil rifles, and in the early days of WW2 the USMC did purchase a small lot of 100 or so as ‘hunting rifles’ for use in the South Pacific. I am not sure what large animals they expected to find on those islands (other than Japanese soldiers) where nothing larger than wild pigs and dogs live, but the purchase is in the archive records and clearly slid by the Ordnance Board as okay. Of course later, frustrated with the wait for their Garands, they also purchased a bunch of Johnson rifles (and LMGs) which use the same bolt mechanism design as the Model 8.

that is the best design of a rifle I have ever saw I would take that old rem 25 over a new colt m4 anyday