“[A] quiet little Yankee who sold himself in relentless slavery to his idea for six weary years until it was perfect” – John Hay, secretary to Abraham Lincoln

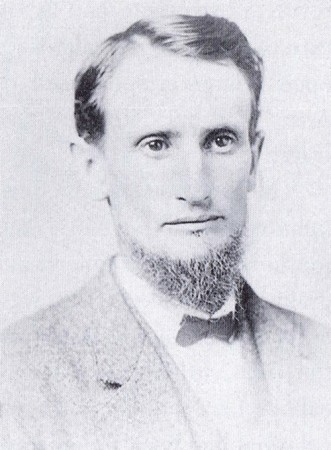

Christopher Spencer was born on a farm in Manchester, Connecticut on June 20th, 1833, the son of Ogden Spencer and Asenath Hollister. At the age of 12 (in 1845), young Christopher moved into the home of his maternal grandfather Josiah Hollister, than 90 years of age. Josiah was a veteran of the American Revolution and a gunsmith, and he nurtured and encourages Christopher’s interest in firearms and machinery. One of his favorite pastimes was working with his grandfather’s old foot lathe, making intricate knick-knacks of wood. His grandfather also gave him his first firearm, a Revolutionary-era musket. In a classic example of the American spirit of tinkering, he immediately sporterized it, sawing off the barrel to make it handier for hunting (yes I can hear all the collector’s cringing at the thought – but wouldn’t you like to have it today anyway?).

At the age of 14 (in 1847) Spencer left home to work as an apprentice in a local silk mill owned by two brothers, Charles and Rush Cheney – who would be close partners with him for many years to come. This initial employment lasted barely a year, and in 1848 Spencer took on a more advanced apprenticeship with machinist Samuel Loomis in Manchester Center, CT. It seems quite likely that this apprenticeship was taken with the blessing of the Cheneys, for at its conclusion he returned to work in their silk mill. It is also worth noting that the winter of 1848 was the only time Spencer spent in school – 12 weeks in the Wilbraham Academy in Massachusetts.

With the experience of his work for the Cheneys and his machinist’s apprenticeship, Spencer’s mechanical genius really showed itself. His real passion, I suspect, was machines to make things – not necessarily the final product itself. Working for several years in the Cheneys’ silk mill, he developed several new machines, as well as showing a real talent for repairing and maintaining machinery. He did wander out form under the Cheneys’ wing to expand his understanding with stints working in other shops, including the New York Central Railroad locomotive repair shop, the Ames Manufacturing Company (a sword and cutlery maker) and a year working for Colt in Hartford.

Returning home from Colt with some newly-planted ideas for improved firearms designs, Spencer went back to work for the Cheneys, this time as superintendent of their new shop in Hartford. He was clearly quite at home in this environment, as he spent 11-hour days in his formal job (including inventing and patenting silk winding machine which they Cheneys sold quite a few of, and paid him a royalty on), and then spent his spare time tinkering in the shop with his ideas for a repeating firearms which would eventually become the 1860 Spencer rifle. He made a wooden mockup of the gun in 1857 (sadly, this first model appears to be lost to time). Spencer’s father Ogden financed the initial prototype (which ended up costing $293.67 to make) in exchange for a 50% share of future profits, and when the Civil War broke out the Cheney brothers became very interested in producing the gun for military contracts. They bought the patent from Spencer for $5000 and a royalty of $1 per gun sold.

Spencer spent the next several years working on the improvement, production, and marketing of his rifle (including a personal shooting demonstration with then-President Abraham Lincoln). The design was a good one and well-suited to the desires of the US military at the time, but by the late 1860s it was clear that the Spencer could not keep us with newer and better guns like the Winchester 1866, which allowed significantly faster shooting and reloading. In 1868 the Spencer rifle company was near bankruptcy, and was purchased by the Fogarty Repeating Rifle Company, not so much for the Spencer rifle but instead for the company’s machinery. Fogarty’s venture flopped, and in April 1869 its assets were all bought up by Winchester, including (ironically) several thousand unsold Spencer rifles and carbines. Right at this time the French government was desperately looking for arms after their disaster at Sedan, and Winchester promptly sold them every last Spencer it had in the warehouse (among other guns).

Spencer had not been a partner in the company (being paid royalty instead), and bounced right back from its failure. In 1866 he began a new venture with Sylvester Roper to make revolving-magazine shotguns. The guns proved too expensive to be a commercial success, and the company and its assets became Billings & Spencer by 1872, engaged in making commercial forgings and sewing machine parts. Spencer continued to indulge his mechanical interests, with an 1872 patent for a new single-shot rifle and work in the 1880s with Roper (again) on a pump action shotgun.

Ultimately, his fortune was secured by the invention of an automated screw-making machine – a device which also guaranteed his name a place in the history of industrial development. With age and wealth he finally relaxed a bit, spending time with his wife and children and continuing to tinker. He built a steam-powdered automobile in 1901, and was dabbling with aeronautics when he died at his home in Windsor Connecticut on January 14, 1922.

Christopher Spencer was one of the stereotypical 19th century American inventors who had no need of formal education and simply believed that an individual’s drive to invent and experiment could bring about wondrous new possibilities. He was always in the shop getting his hands dirty, and it made him a wealthy man.

Bibliography:

Case, Lafayette Wallace M.D. The Hollister Family of American. Hartford, Connecticut, 1886.

Bilby, Joseph G. A Revolution in Arms. Westholme Publishing; Yardley, Pennsylvania, 2006.

Be the first to comment