The first rifle produced by Armalite began in 1952 as a project between the brothers-in-law, Charles Dorchester and George Sullivan (no relation to later Armalite engineer L. James Sullivan). Sullivan is the chief patent attorney for the Lockheed aircraft company, and the two have the idea to produce an ultra-light rifle using aircraft industry materials like fiberglass and aluminum. They create a company called SF Projects and get to work using Remington actions. They fit aluminum (and then later aluminum/steel composite) barrels and foam-filled stocks and the result is a rifle that weighs less than 6 pounds with a 4x scope fitted. The first ones are chambered in .257 Roberts, but this shortly gives way to the new .308 Winchester cartridge.

Sullivan and Dorchester make a connection with Richard Boutelle, who is very much a “gun guy” himself and also head of the Fairchild aircraft company. The idea of the rifle appeals to Boutelle, and Fairchild was looking to diversify its operations – and so Fairchild agrees to buy SF Projects, renaming it the Armalite Division of Fairchild.

The idea of the rifle was for civilian hunters who want a gun that is light to carry for long distances and also military specialists like airborne troops who need lightweight gear. The Army tests the AR-1 in 1955 and finds some fairly serious problems with it. There are reliability issues, and also accuracy shortfalls. When the composite barrel heats up, differential stresses cause the point of impact to shift. This foreshadows the catastrophic failure of a composite barrel in AR-10 testing, but that is a story for another video. Ultimately after two rounds of testing the Army rejects the rifle, and that is pretty much the end of it. Armalite moves its focus to other projects, namely combining aircraft industry materials with the self-loading rifle of their other designer, Eugene Stoner. That, of course, will become the AR-10.

Since I know folks will ask, the AR projects between 1 and 10 were thus:

AR3: Stoner-type rifle in hunting configuration

AR5: Air Force survival rifle

AR9: Shotgun

The designations 2, 4, 6, 7, and 8 were set aside to drawing board projects that never materialized.

Thanks to the Springfield Armory National Historic Site for giving me access to these rare specimens from their reference collection to film for you! Don’t miss the chance to visit the museum there if you have a day free in Springfield, Massachusetts:

https://www.nps.gov/spar/index.htm

The AR-7 was marketed as a floating survival rifle back in the 1960’s. My brother had one. The design has been sold a couple of times, and I think Henry now makes it. I was out with it one day, and had a failure to feed. Being trained on the M-1, I slapped the bolt handle forward. The round went off in the ejection port, and the bullet got stuck in the barrel. I pulled a bullet from a case, and put the case full of powder in the chamber, and it fired with a low “pop”.

In my experience with Charter Arms-made AR-7 rifles and Explorer II pistols, they work pretty much perfectly with high-speed .22LR with round-nosed bullets (solid or hollow-point). They do not work with truncated-conical bullets (Remington Yellowjackets). They absolutely love CCI Stinger RN HPs.

I might add that in spite of that threaded-on barrel setup, once the sights are dialed in for the ammunition in use, both rifle and pistol are surprisingly accurate out to about 75 yards.

Also, the AR-7 action is one of the few . 22s that can be conveniently operated left-handed. In fact, due to the offset of the stock attachment, it’s easier to get your eye behind the peep sight on the rifle firing from the left shoulder; you can hold your head almost perfectly upright rather than having to crane it over, as when firing right-handed. The safety is more easily manipulated by the left thumb, as well.

clear ether

eon

Back then, I was using Remington hollow points. They usually worked. I do not remember an offset on the originals. I am left handed, and had no trouble. I agree about the range. Sights are basic.

“(…)rifle was for civilian hunters who want a gun that is light to carry for long distances(…)”

And how well it worked in term of sales?

Poorly.

The one thing I’ve observed over the years is that the vast majority of these “ultralight” rifles wind up as safe queens, or out on the resale racks. Everybody loves the idea of “light and easy to carry”, right up until they actually fire one. Then, the twin gods of recoil energy and inertia take over, and lessons are learned.

You rarely see people carry these lightweights out hunting for more than a season or two; ’tis a grand idea for your youth, but then you get older and the shoulders become a lot less enthused about actually firing one of these enough to get really good with it, or even routine zeroing.

Friend of mine bought one of those carbon-fiber wonder guns a few years back. Carried it for one season; got two elk and a couple of deer. Does not carry it any more, and flatly refuses to even take it out of the safe, these days. He is now hunting with “retro-rifles” exclusively, the big heavy beasts of his forefathers. Their mass soaks up the recoil, and he’s not moving around as quickly as he once did, so the “excess” weight doesn’t bother him.

There are a lot of things in firearms design that are attractive and which seem like a Really Good Idea(tm), right up until you run up against the accompanying realities of executing those Really Good Ideas(tm). Then, you’re suddenly struck by the wisdom of your elders, and recognize that the TANSTAAFL principle applies everywhere.

(TANSTAAFL=There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch)

As a general rule, I refuse to fool around with any rifle weighing much less than 9 lbs, other than ones firing intermediate cartridges with low recoil impulse. I prefer to (A) actually hit what I’m shooting at and (B) not have a black-and-blue shoulder after the fact.

The same holds true for SMGs on full-auto. Anyone who thinks the old MAC 10 didn’t need that sound suppressor just as a foregrip never tried to fire one on full without it. Most 2nd generation (WW2 type) SMGs were almost too light to be controllable, notably the Sten, M3, and MP40. The TSMG’s weight was “just about right” for reasonably effective full-auto fire with .45 ACP.

The M2 Carbine was right on the borderline in full-auto fire. Largely due to its lower recoil impulse compared to the blowback SMGs.

In bolt action or etc. rifles, I put the lower weight limit for .308 Winchester class cartridges at about 8.5 lbs empty weight, not including optical sights. .300 Magnum class? Not under 11 pounds.

“African game” class cartridges? .375 to .416, not under 12 pounds. .458 on up, 14 pounds, minimum.

Add one pound to all caliber classes if the cartridge says “Weatherby” (WBY) on the headstamp. The .30-378 supposedly outperforms the old .300 Weatherby with 200-grain bullets- with lower recoil. I remain to be convinced. I suspect this was why not too many Howa-made Vanguards were made in .30-378. (The Vanguard Synthetic is a very nice rifle- in .308 Winchester.)

I suspect this was also why the various “Super-Short Magnums” didn’t catch on. The idea of putting the equivalent of a .300 Winchester Magnum or 7mm Remington Magnum into a cartridge case short enough to work in a .308-length action, and a rifle under 8 pounds dry weight, might look good on paper. But when actually using it, it’s a different story.

clear ether

eon

Yeah, never understood the “.30 at all costs” thought process. I figure if you want a nice light, handy deer rifle, even going so far as 7 pounds and change, there are plenty, it’s just not going to be a long-action .300 with moderate to severe magnumitis, it’s going to be a .257 Roberts or something in that range

The 1976 Gun Digest may be where it got started. Specifically the article “The Practical Light Sporter” By James Ott on pp.154-160.

In it, Ott described what he and others at the time dreamed of as a lightweight “sheep rifle” for mountain hunting. Start with a lightweight action (the Czech 33/40 was favored back then), put a light sporter contour barrel on it, the lightest telescopic sight available (The Bushnell Custom 3X-9X was typical), and do all sorts of tricks like routing out spaces in the forearm, drilling holes lengthwise through the buttstock, and even drilling out the sides of the magazine box with lightening holes.

The end result was supposed to be a rifle which, with sling, scope and a full 5-shot magazine, should not weigh more than seven and one-half pounds. Easy to get up and down hills with when slung (lightweight nylon sling, of course).

What rather negated the whole exercise was that since they wanted to hunt the likes of Dall sheep from one crag to another, they needed cartridges with high velocity for both range and as flat a trajectory as possible. Their choices started with .270 Winchester and .280 Remington, and went on up to .30-06 and 7mm Remington Magnum (no, seriously). Any of these could certainly bring down a ram at 400 meters, but none of them would be any great pleasure to touch off in a rifle barely heavier than a Savage 99 lever-action carbine without a scope (7 pounds in .300 Savage or .308).

Ironically, back on pp. 115-121 of the same annual was a reasonable answer to the problem. “The 6.5 x 55- An Old Swede” by Emil S. Piraino. It goes into why the 6.5 x 55mm Swedish Mauser was for most of the 20th century as popular in Scandinavia as the .30-06 was in North America. Reason? Performance roughly equivalent to .270 Winchester with comparable bullet weights, in a shorter cartridge with less recoil.

Bullet design was the key. The .270 is normally loaded with flat-base bullets that are basically 90% scale copies of .30-06 projectiles. The 6.5 was and is normally loaded with boat-tailed bullets with a greater length compared to diameter, thus a higher fineness ration and lower base drag.

As such, if yo fire a 160-grain .270 and a 160-grain 6.5 x 55 side-by-side, the .270 will start out at about 2,800, while the 6.5 x 55 will leave at about 2,600- 200 F/S slower.

But since the flat-based .270 bullet sheds velocity more quickly than the boat-tailed, better fineness-ratio 6.5mm slug, at about 350-400 meters downrange, both will be moving at almost exactly 2,400 F/S, with almost identical trajectories and energy. In short, out where the real business is done, there is no practical difference between the two.

Except that the 6.5 x 55 doe not require a .30-06 length action. And has less recoil than the .270.

The 6.5 x 55mm would have been a better choice for their “Practical Light Sporter” than the .270. Just as .308 would have been a better option than .30-06. For that matter, the old 7 x 57mm Mauser, or the then-new 7mm-08 Remington (Basically a .308 necked down to 7mm and loaded like the 7 x 57), would have all been better choices for a “light sheep rifle”. Within a practical range of 400 meters, the sheep would not notice the difference when it got hit.

I can only conclude that back then, Gun Digest writers did not bother to read each others’ articles before sending them off to the printer.

And even today, a lot of people- even hunters- tend to believe anything “authoritative” they read.

PS- Yes, I have owned and used everything from .300 WM to 7.9 x 57, .308, and everything in-between in the rifle-shooting department.

Even today, when I need a bolt-action, telescopic-sighted rifle,

the one I get out is a sporterized 6.5 x 55mm Swedish Mauser, Fajen Premier Grade Monte Carlo walnut stock, Williams iron sights, and with a Bushnell 3X-9X scope in Weaver rings and bases. I bought it over three decades ago, and still consider it well worth the $155 it cost me at the time.

cheers

eon

Oh, and PS;

With a military leather sling, which I prefer for actual shooting, and five rounds in the magazine, it weighs exactly nine pounds and five ounces.

cheers

eon

“(…)refuse to fool around with any rifle weighing much less than(…)”

I thus have inverted question. What cartridge could be used in AR-1 to make it acceptable recoil-wise while keeping overall mass same. Would .243 Winchester would be okay? If yes then AR-1 would be probably another example of bad luck w.r.t. timeline as according to https://guns.fandom.com/wiki/ArmaLite_AR-1 its’ development finished in 1954, whilst .243 Winchester was introduced in 1955.

The .25 Remington (introduced 1906) would have been a good choice- if Remington hadn’t dropped it during WW2 and the ammunition maskers hadn’t discontinued the cartridge around 1950.

The .32 Remington would have been a similarly reasonable choice- but it met the same fate as the .25 about the same time.

(Both were rimless ballistic equivalents of existing rimmed rounds; the .25-35 Remington and .32 Winchester Special, both designed for use in tubular-magazine repeaters.)

The in-between .30 Remington was available, but it was a ballistic twin of the .30-30 WCF. Which sort of ruled it out for anything beyond about 200 meters.

Pretty much none of the “wildcats” of the era would have been suitable. The primary distinguishing characteristic of those was everybody wanted a MV as close to 3,300 F/S (~ 1,000 M/S exactly) as they could get. Never mind that that sort of velocity (1) demands a heavy powder charge and thus generates high breech pressure, (2) also generates high bore pressures and temperatures, (3) causes excessive bore wear with the barrel steels of the time, which will burn the rifling out at the leade’ in about 1,000 rounds and make the barrel a smoothbore in about 3,000, and (4) generally do not deliver even acceptable accuracy at even moderate ranges, let alone the half-mile or more (800-900 yards/800 meters) the accuracy bugs were obsessed with.

Pretty much every “wildcatter” touted the Wowie-Zowie Factor. “My wildcat goes faster and is more accurate at a thousand yards than anybody else’s!” And most of them didn’t know WTF they were talking about.

The problem was that going back to the beginnings of the small-bore (under .35 caliber), high-velocity (over 2,000 F/S) era with the advent of smokeless powders (1890s), velocity was the Holy Grail. That’s how we ended up with first the 6mm Lee Navy (1895; 112-grain @ 2,560) and its offspring the .220 Swift (1935; 50-grain @ 4,111 and no, that is not a misprint). Both developed by Winchester and both noted for destroying barrel rifling in under 1,000 rounds. So it wasn’t just “wildcatters” who came down with bad attacks of stupid. (Regarding the 6mm, Naval BuOrd should have had some explaining to do…)

The fact is that there just was no then-current sporting rifle cartridge in the U.S. that would have made the AR-1 a viable proposition.

Going to foreign cartridges, there were several 6.5mm class military and/or sporting rounds that might have been suitable, such as the 6.5 x 55mm Swedish I mentioned, the 6.5 x 50mm Arisaka, or the 6.5 x 54mm (Austrian) Mannlicher-Schoenauer. But their average MVs (under 2,600 F/S) with virtually all loadings just weren’t “Wowie-Zowie” enough to interest anybody who designed rifles.

Pretty much all British or European commercial cartridges of the era can be ruled out as well. If they were under .35 caliber, they were launching projectiles at over 2,900 F/S. And most of them were “magnums” in both performance and cartridge dimensions; not something to put in a rifle weighing under 10 pounds if you valued your shoulder.

Looking at the whole tangled mess, it shows that the smartest thing about the U.S. Army’s “Lightweight Rifle” program that resulted in the AR-15/M16 family was that they developed a brand-new cartridge, the .223 Remington aka 5.56 x 45mm first. Based on what they wanted the rifle to do.

And then designed the rifles around that.

cheers

eon

@eon,

I think one of the bigger problems with the ammo was cultural; you had all the “experts” that were anointed by the gun press who were enthusiasts of “mo’ bettah” velocity and power, yet who really did not understand ballistics very well.

As you point out, the 6.5 Swedish was better at range because it had a better projectile. Few, if any of the authority figures paid attention to that fact, and neither did many of the wildcatters whose work led into new cartridges.

I’d observe that the ideal cartridges for many purposes were already out there, and had indeed even been abandoned in the name of “improved” stuff that’s not really all that improved. Any of the recent “short magnum” cartridges are examples of “marketing churn” more than they are anything else. The majority of them just plain suck for actual real-world shooting, and most of the people who fell into the whole thing following that scam are now back shooting “traditional” cartridges for various reasons.

The whole thing is a bit of a “black art”, when you compound marketing, consumer perception, and actual black-letter ballistics. Look at the idiocies surrounding the whole NGSW fiasco… The original idea was to get a lighter, more effective round out there for the troops, something like the cased telescopic or caseless solutions that were seen as “good ideas” early on. What’d we get? The ultimate expression of “mo’ bettah velocity”, which I strongly suspect will fail miserably in actual combat.

Have to wait and see, on that one. I can only hope and pray that we don’t lose too many good men relearning the lessons we should have taken from WWI combat.

Again.

The market in the CONUS (and in ZA and NAM) would have been quite limited both then and now. Most of us who take the time to hike in for a hunt for half a day or more use bows or just understand that carrying an extra kilo on the way in will be trivial compared to the weight you hope to be carrying back after a successful hunt.

I coud not agree more to what kirk and eon wrote about the “light hunting rifle” pipe dream.

Now after some thinking I wonder about yet another thing w.r.t felt recoil. AR-1 has exotic (for 1950s) furniture (fiberglass), how did it compare in area of stiffness when compared to 1950s U.S. wooden rifle’s furnitures? (I presume if it was more stiff, then it made recoil even more unpleasant than just smaller mass imply)

Considering the trouble Winchester had with fiberglass stocks on their shotguns back then, I suspect the major problem would have been the stocks failing under load. Think “fracturing at the recoil bolts”- level failure.

Not to mention just basic “gross fragility” (i.e. not standing up to being “bumped around”) as was seen with the early olive-green fiberglass stock/forend/pistol grip material on the M16.

Again, the smart thing would have been to go to the experts (in this case, the plastics and chemical industry, i.e. DuPont & Co.), tell them what the stock would have to stand up to, and ask them to come up with a plastic or etc. material that would do the job.

Considering what they were working on at the time for other reasons (Callery Chemical was getting interested in boron nitride as aerospace materials after the whole boron-based “Zip fuels” program went belly-up in 1954), they might just have come up with something twenty years earlier than they did historically.

Imagine an A6 Intruder or F-111A with graphite-composite structures in 1959-62. Or even B-52s with composite wings and tails.

It just might have changed the “flavor” of paddy strikes. To say nothing of Rolling Thunder.

cheers

eon

I was at the National Matches at Camp Perry in 1967. We were introduced to the M-16, but only given 10 rounds each to try them. Weighed nothing. Green plastic. No forward assist. I got into a tight prone sling, and the sergeant yelled at me because I might bend it. It went “BOING!” when fired. Cigarette burns on the stock. I wasn’t impressed, and went back to my brand new National Match M-14. And took 2 silver medals with it.

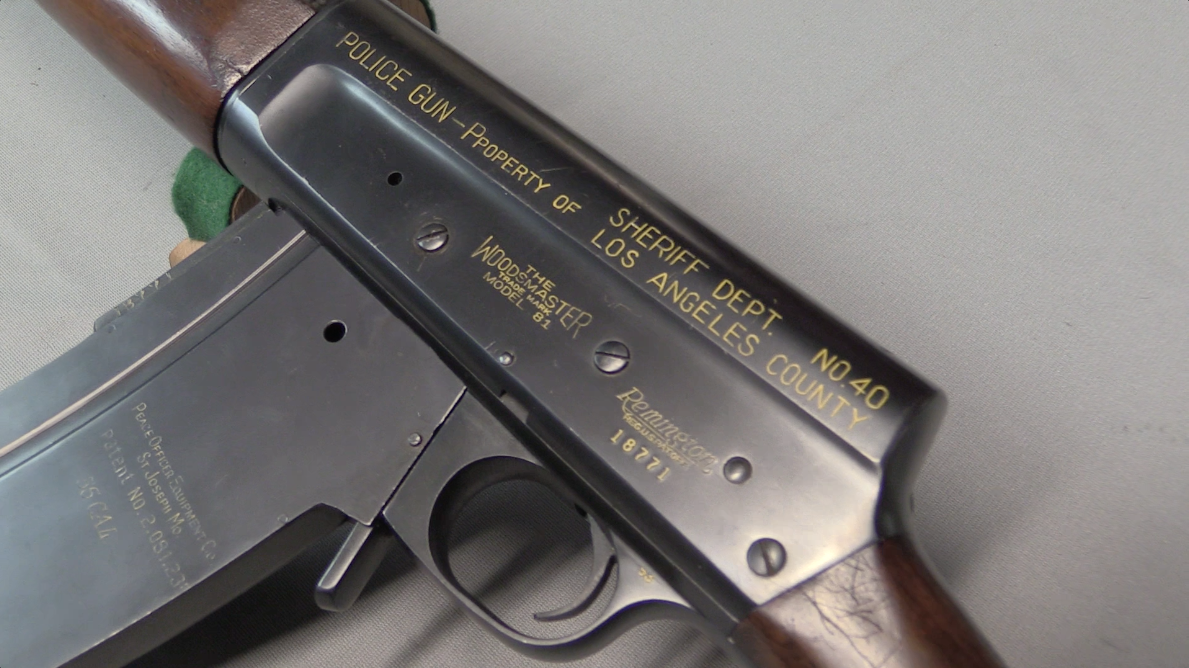

Just have to know how the yellow paint got on those guns and why its still on there?!

Yellow paint is on there because that’s what they used during testing to identify rifles and do things like provide marks for high-speed cameras to reference, as well as lining things up in test rigs.

Or, so I was told. Your mileage may vary, and other information is no doubt available.

It’s still on there because that’s how museum curators conserve their specimens; they rarely do restoration work, just keep things as they were when they were turned over to the museum.