The movie industry has always had special requirements for firearms. Flintlocks, for example, can be rather finicky guns for folks to use without practice and care, and that does not work will in a filming environment where a whole scene’s setup would be wasted it a flintlock fails to fire properly on demand. Today, courtesy of Mike Carrick from Arms Heritage magazine, we have an example of an old solution to this problem: use a thoroughly reliable cartridge-firing Trapdoor Springfield and just make it look more or less like a flintlock. Guns like this one were used in a variety of movies, including specifically the 1953 picture “The Man From the Alamo” and John Wayne’s 1960 film “Alamo” (in Wayne’s film, the same system was also used to make mock Kentucky rifles).

Related Articles

Conversion

Merrill Breechloading Conversion of the 1841 Mississippi Rifle

Lot 1171 in the September 2020 RIA Premier auction. James Merrill of Baltimore had his hands in several Civil War era firearms – rifles built from scratch, conversions of the Jenks carbines, and also conversions […]

Reproduction

LugerMan Reproduction of the 1907 .45 Test Trials Luger

Eugene Golubtsov, aka LugerMan, is manufacturing reproduction .45ACP caliber Luger pistols, based on the original blueprints of the 1907 pattern US Army trials guns. When he offered to send me one to try out, how […]

Fake

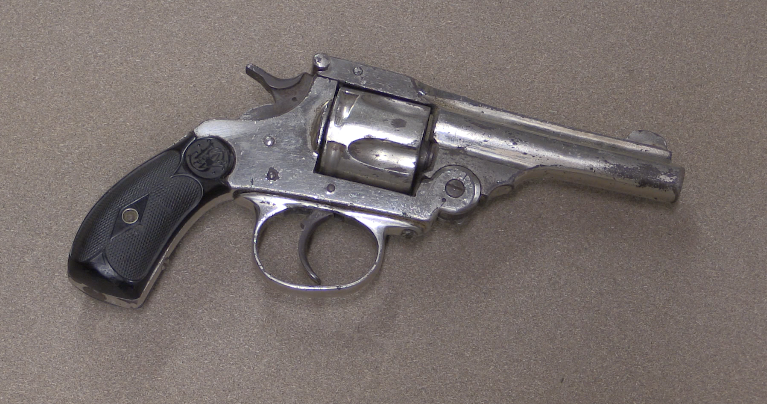

Smill & Welson Spanish Counterfeit Revolver

This revolver looks like it is a Smith & Wesson DA from the early 20th century, right down to the S&W grips. However, it is actually a Spanish Eibar-made copy, and you can tell when […]

Old Soviet films like “War and Peace” (Voyna i mir, 1965 ) used Mosins and even Berdan rifles modified in similar ways to these trapdoor Springfields to stand in for flintlocks in the huge battle scenes.

Even more curious are the fake M16s in Soviet movies, made from Stgw 44:

http://www.imfdb.org/wiki/Pirates_of_the_XXth_Century#Sturmgewehr_44_.28visually_modified_to_resemble_M16.29

Well, I guess improvise adapt overcome fit here well. Take closer look at what is supposed is to be Thompson gun in hands of U.S. gangster from 1980s comedy: http://www.imfdb.org/wiki/D%C3%A9j%C3%A0_Vu_(1988)#PPSh-41_.28Mocked-Up_as_M1921AC_Thompson.29

This affected not only weapons but also vehicles, take for example

https://foxtrotalpha.jalopnik.com/why-is-this-mi-24-hind-wearing-u-s-coast-guard-colors-1644434863

Well nobody is going to get a scrutinized closeup of the lock work during the shooting scene, so this mockup does the mimicry sufficiently. Just remember to reload offscreen.

I think IMA had a couple of these for sale not to long ago and I actually remember seeing them in old movies when I was little and thinking that they were “cheating” and using the wrong type of gun without considering the reliability factor. I may have seen them in Drums Along the Mohawk and I think some of the conversions even had an opening near the breach to provide a puff of smoke back there like a real flint lock (probably wouldn’t want to fire live ammo in those)

Over here in France they even had one of those childrens dart firing rifle with a stamped metal flintlock on the side I believe it was called a Davy Crockett The american television show of the same name and the song dubbed into french were very popular in France

Here you go-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=csUZHU04M5E

I remind this style of prop guns from Disney’s old Zorro show.

If memory serves, there were even pistols in the same style.

One detail that this prop would fail at is there would be no flash and puff of smoke when the priming powder is set off in the frizzen. I’m not familiar with firing a flintlock myself, but I’ve seen Disney’s DAVY CROCKETT and they apparently used real flintlocks which gave a spectacular flash of smoke at the lock when the rifle was fired.

I googled the old IMA listing for a fake jezail/trapdoor conversion and you can see what looks like a small pipe or channel along the breech and an opening by the frozen for just such an effect but it doesn’t look like the one Ian looked at has the same so different studios may have down different conversions (I was also wrong about which movie I was thinking about seeing when I was young. It was Northwest Passage that had these fake flintlocks/ trapdoors)

“(…)no flash(…)”

Note that currently this might be added in post-production, in way similar to muzzle flash, read for example https://fxhome.com/blog/how-to-create-realistic-muzzle-flash-effects

Similarly, several Canadian re-enactor groups use breech-loading Snider Lee_Enfield conversions: Fort Henry Guard, Fort York Guard and Sherbrooke Hussars Centennial Guard (only 1967).

Every summer they re-enact parades and military life from the War of 1812 or to commemorate Canada’s Confederation in 1867. They march around, change the guard and fire volleys with black powder blanks. Since Sniders were only introduced during the 1860s, Sniders are too young for the War of 1812 and barely plausible for 1967. Remember that colonies only got new rifles after the British Army.

Canada received its first Sniders in 1867, the year after it was officially adopted in the UK. We were high on the priority list for them because of the problem with cross border insurgency and terrorism from the US involving a number of different groups, which was a constant throughout most of the 19th century. The 1866 Fenian Raid gave particular impetus to acquiring Sniders.

The first shipment of Sniders to Canada consisted of 30,000 rifles which arrived in 1867 and first saw action in the 1870 Fenian Raid.

So, the Canadian militia having Sniders is 1867 is historically accurate.

Canada in the 19th century was an area of regular military conflict, both externally (with the US or US based insurgents and terrorists) and internal rebellion, as well as repeated narrowly averted wars with the US. The militia therefore saw regular active service and were equipped accordingly. This wasn’t the case in many other colonies, who were therefore lower on the priority list for getting the latest kit. For example, Canada ordered its first Lee Enfields the same year that rifle was adopted by the UK, due to the Venezuelan border crisis potentially leading to another war with the US. The desire to be ensured of getting the latest arms is what led to the Ross Rifle being adopted, as Sir Charles Ross was willing to set up production in Canada.

For the front sight, I think it’s legitimately a practical necessity instead of for the camera that wouldn’t see it. Some of the later Star Trek phasers skipped having sights (the really early ones instead for main characters did have tiny sights), then readded them after it became clear in post the actors couldn’t point their weapons in remotely the right direction without them.

S&S has had the hammers listed for years, but I’d never seen them applied until now. Definitely an innovative compromise between performance and cost; if Michael Bay made the movie now they’d use ARs and tell the two viewers over the age of 12 to suck it.

There’s another episode to do on five-in-one blanks.

Indeed – in the John Wick films the select fire and semi-auto weapons were fully blocked a way back from the muzzle and quite low power blanks were used simply to generate visible cycling and ejection. Muzzle flash was added later. Even in guns with restricted rather than fully blocked barrels in the early days the blanks had to be specially made with aluminum powder added so the flash lasted long enough for the cameras to pick it up. Cheaper to add as much flash as you want after the actors and film crew are no longer on charging time!

That last of mine was supposed to follow Daweo’s comment

Back in the 1940’s and 50’s they didn’t have CGI technology to add flashes from frizzens during post production. If you google the jezail that was at International Military Antiques (it is sold but still shows up if you search for it), you will see that there is a contraption to duct the burning powder from just ahead of the chamber back to an opening back by the fake frizzen. This would provide the flash and smoke to make the firing look more like a real flintlock. That gun at IMA was used in Gunga Din but the one that Ian looks at doesn’t appear to have a similar contraption so maybe they weren’t too worried about gun geeks like us saying “hey, where’s the frizzed flash?” I would imagine most of the movie viewing public has no idea about the difference between a flintlock and a later gun beside the fact that you loaded from the far end (the actors handle pretending to muzzle load) and that there was some extra stuff (the frizzen) back by the lock but evidently some other production companies did try to make their fakes more realistic.

“(…)maybe they weren’t too worried about gun geeks like us saying “hey, where’s the frizzed flash?””

More generally older movies often follow more symbolic convention, where less effort is delegated to keep with technical details. Battle of the Bulge from 1965 portrays Unternehmen Wacht Am Rhein, which was done in snowy winter of 1944/1945, though I doubt most of audience would conclude that after watching said movie.