The Australian-designed Owen submachine gun is a weapon with quite a story behind it. The Owen is arguably the best subgun used during WWII, and also probably the ugliest. Its mere existence was a drawn out struggle between the inventor and manufacturer and the Australian Army bureaucracy, and yet it saw service through into the Vietnam War.

History

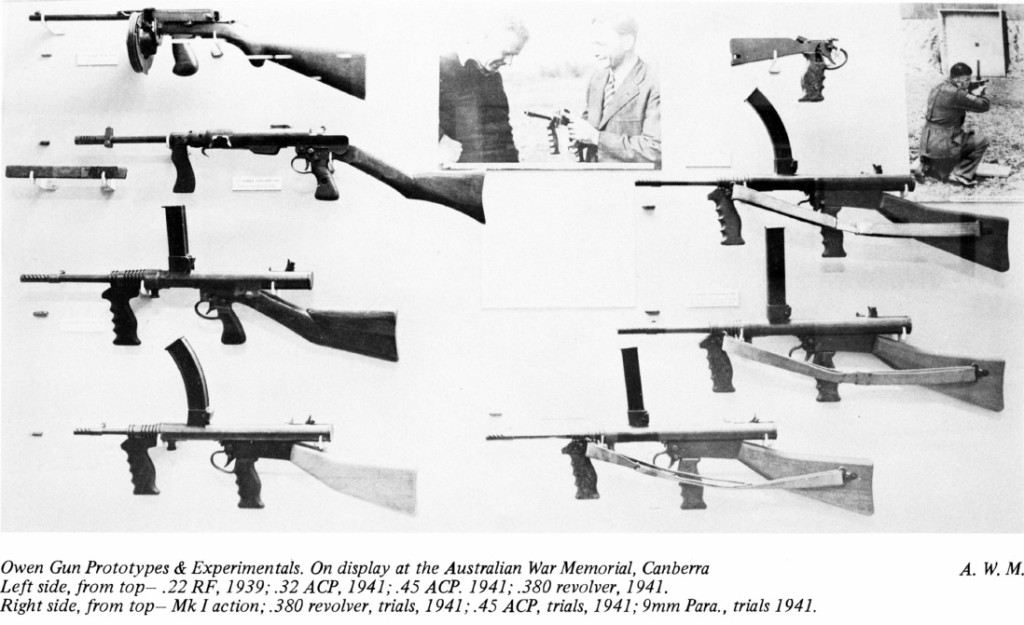

The Owen gun story begins with a young 23-year-old Evelyn Owen and his incessant tinkering with guns. In 1938 he perfected (well, sort of) a homemade full auto carbine firing .22LR from a drum-type magazine. It used a thumb trigger instead of the normal type, and was thoroughly unfit for military use. He showed the gun to a some Australian Army officers in 1939, and was (not surprisingly) turned away – the Army was not interested in new submachine guns in general nor Owen’s contraption in particular. By 1940 Owen had lost enthusiasm for the gun, and enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force.

That would have been the end of the story if not for a happy accident. Shortly before deploying for military service, Owen haphazardly left his prototype gun in a burlap sack leaning against the house – where it was subsequently found be a neighbor (Vincent Wardell) who just happened to be manager of Lysaght Works, a metal fabrication firm. Wardell was curious, discussed the gun with Owen, and convinced him to demonstrate it to the newly formed Army Central Inventions Board. The Board commander , a Captain Cecil Dyer, was interested (the Battle of France having been recently lost, and Britain’s ability to prevent German invasion in serious doubt), and the result of the demonstration was Lysaght’s agreeing to develop an improved centerfire version. Owen left for his deployment, and development of the gun was undertaken by Vincent Wardell, his brother Gerard, and a gunsmith in their employ named Freddie Kunzler.

At this time, most of the Australian Army officialdom was anticipating adoption of the Sten gun, plans and models for which had been promised to them by the British government. The Sten was purported to be a much better gun than experience would eventually show, and the establishment didn’t want to muddy the waters with competing designs with no provenance. In an effort to scuttle the newcomer, the Army told Lysaght to provide a sample gun for testing, chambered in .38 S&W (and neither ammunition nor a barrel was to be provided for factory use). The specification of a rimmed cartridge was expected to stump the Wardells, and was indeed a challenge not undertaken by any previous successful SMG design. So they sidestepped it, and made the gun in .32ACP instead, using a section of an SMLE barrel. This prototype was delivered to the Army in January 30, 1940 – after just 3 weeks of development. It fired effectively and reliably, and the Army requested a 10,000-round endurance test. They would not supply the ammunition, and in wartime Australia that quantity was effectively impossible for the factory to acquire. Instead, Lysaght’s built another gun in .45 ACP, having been assured that plenty of ammunition would be available for this (they assumed it would be from stocks supplied for Australian Army Thompson guns). But when the ammunition arrived at the factory, it turned out to be .455 Webley ammunition instead – so they went back again and retrofitted the gun using a section of old Martini-Henry barrel.

Around this time Evelyn Owen was recalled from field duty and assigned to work with Lysaght on the gun development, although it is unclear when design elements were his contributions and which were brought by Wardell and Kunzler. The Army efforts at scuttling the Owen gun continued, and it was only through Vincent Wardell’s persistence and willingness to go directly to civilian politicians that the gun finally came to be accepted. It had passed mud and dust testing with exceptional results in both .455 Webley and .38 S&W (the first 100-gun order was again demanded to be in .38 S&W by the brass). Only in early September 1941 was a 9mm version authorized, and this by a civilian official tired of Army obstructions.

The turning point for the Owen was a competitive trial at the end of September 1941, in which it (in both 9mm Parabellum and .45ACP) was pitted against a newly-arrived Sten and a Thompson. The Thompsons did well when clean but not so well when dirty, and the Sten quickly failed in sand and mud tests. The Owen passed with flying colors, in both calibers. This led to an order for 2,000 9mm Owen guns for field trials, and the rather impertinent sending of Owen gun samples and drawings to England, with the suggestion that the Sten be discontinued in favor of it (and in a 1943 English test, the Owen beat all comers, including the Austen, Sten, and Sterling).

Mechanics

The Owen was a fairly simple open-bolt design, but it incorporated a number of creative elements that made it superior to other contemporary guns.

First of all, it utilized a top-mounted magazine, which gave several benefits. It allowed gravity to assist both feeding and ejection (although the Owen will function when held upside-down). Since the ejection port was on the bottom of the receiver tube, dirt which might enter form the magazine or through the magwell would often just fall right through, having no place to collect.

Second, the Owen used a two-chamber receiver. The bolt cycles in the front chamber (with a relatively short travel), and the charging handle is located in a separate chamber in the rear of the receiver. Only a small hole between the two allows the charging handle to connect to the recoil spring guide. As a result, and dirt entering through the charging handle slot is confined to the rear section, where it cannot do much to impede the gun’s function. There is no way for gunk to get behind the bolt, where it is most apt to cause problems.

Because of this design, disassembly is done from the front – unlike most open bolt subguns. The barrel is easily removed by pulling up on the barrel pin at the front of the receiver. The rear end of the barrel and the front of the receiver tube are machined with tapers, so the barrel is easily seated in place. Once the barrel is removed, the bolt and recoil spring slide out the front of the tube. In most guns, this would be obstructed by the ejector, but in the Owen the ejector is made part of the magazine rather than integral to the gun itself. As the bolt extracts a fired case, it holds the ammunition in the magazine down (well, up, given the top-feed arrangement). After enough rearward travel, the rim of the empty case hits the ejector tab at the rear of the magazine, which tips it out of the extractor to drop free of the gun. Pressure from the next round in the magazine, now pushing directly on the empty case, provides additional ejection force.

Handling

The Owen is a very clumsy looking gun, but handles better than you might expect. The grips are well placed, the weight (9.5-10.5 pounds, depending on the version) and built-in compensator at the muzzle help to keep the gun controllable. The safety and magazine catch are both simple and effective (although the original fire selector apparently had a tendency to allow bursts when in semiauto mode). To allow for the top-mounted magazine, the sights are offset to the left side of the gun – not a problem for a right-handed shooter, but a bit of a handicap for lefties.

The stock design is not particularly ideal, and is somewhat reminiscent of the Thompson (I have no evidence to prove it, but I would suspect this was deliberate, since the Thompson was the SMG in official Australian service when the Owen was being designed). Combining the Owen’s positive features with a stock design more in line with the bore could have made for a very interesting gun (in fact, the Australian F1 SMG that eventually replaced the Owen did this to some degree).

Variants

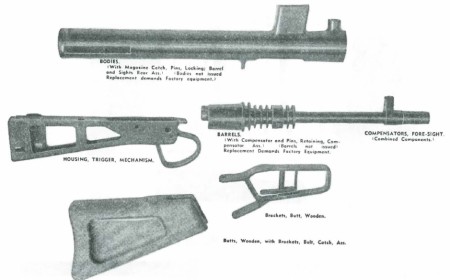

The Owen went through several changes, although the basic mechanism remained the same throughout production. The main goal of the changes was to reduce the weight of the gun, and they were able to take more than a full pound off of it this way. Guns made during WWII were painted with a camo scheme of green and yellow for jungle use, which is often seen on guns today. After the war, guns that were arsenal refurbished had the paint stripped off and were parkerized.

The two main versions are the Mk1 (roughly 12,000 made) and Mk1* (roughly 33,000 made). A MkII version was designed, but only a few hundred made. In theory, parts between all the Mk1 and Mk1* guns are interchangeable, although factory QC was not always tight enough to make this true in closely fitted parts like barrels. Over the course of war use and several decades of official adoption, many existing Owen guns will have a mixture of parts from different official types.

The main parts that were changed were the trigger housings, barrels, and buttstocks.

The early barrels were quite heavy, and finned to aid cooling. Over the course of production they were lightened and the fins discarded. The slotted muzzle compensator remained a feature of all versions, though.

Trigger housings began as solid units, and were later lightened with cutouts to remove unnecessary material.

The original buttstock design was made of bent strip steel, and a later version was made with a clip to hold an oil bottle. Wooden stocks were also made, both solid and with lightening cuts and both with and without traps to hold cleaning equipment.

Center – Factory rebuilt Owen with Parkerized finish, plain light barrel, and wood stock

Bottom – Austen SMG for comparison

Legacy

The Owen was taken out of production in 1944, with 45,433 guns built. They would remain in Australian service until replaced by the F1 submachine gun (which we will cover in another article) in the late 1960s. Owens saw use in Korea and Vietnam, and were generally well liked by troops who carried them. The gun may have been heavy, but it was rugged and dependable.

Evelyn Owen, unfortunately, did not lead a happy life after the war. He became addicted to alcohol, and died a bachelor in April 1949. Aside from employment and salary, he received payment of about £10,000 pounds for his part in the Owen gun production (royalties and patent rights sales), which he used to set up a lumber mill. He did continue to tinker with firearms until his death.

The Lysaght Works began the Owen gun project as a patriotic endeavor to help ensure Australia’s survival through the war. Until the first major order for 100 guns in April 1941, the company funded all the development and prototype construction itself, not asking for reimbursement. When mass production was contracted, payment was agreed at cost plus 4%…but government payments were perpetually late, and Lysaght was not paid in full until 1947, three years after production ended. After making additional interest payments on loans that could not be paid on time because of Army delays in payment, the company ended up making approximately a mere 1.5% profit on the project.

Technical Specs

Caliber: 9×19 Parabellum

Mechanism: Unlocked (blowback)

Overall length: 32in (813mm)

Barrel length: 9.7in (247mm)

Weight (late): 9.3lb (4.2kg)

Magazine capacity: 32 (some sources say 33) rounds

Rate of fire: 700-800 rpm

Video

I had the chance to shoot an Owen, but only briefly – and I did not have a chance to get any video of the internal mechanism. But you can see it firing:

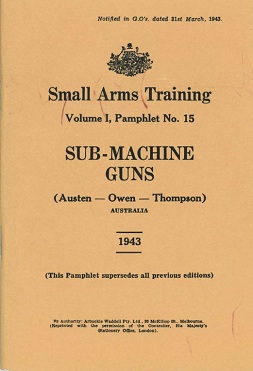

Manuals

We have a copy of a 1943 Australian submachine gun manual, which covers the Owen as well as the Austen and the Thompson. It is short, but includes quite a bit of good information (note how doctrine at the time included shooting from the hip). You can down load it in PDF format here:

A neat design.

I wonder how it compared in reliability to the Sterling, because those guns were freakishly light.

I should clarify that, yes, I read that it was compared in 1943 to a Sterling, but I’m certain that was a prototype Pratchett, and I wonder if the later guns compared more favorably.

I would guess that it was in a class of it’s own. In Canadian tests, the Owen continued to function despite firing 7 mags with a simulated sand storm blowing from the left, and five mags from the right. It was even plunged muzzle first into mud, pulled out, and fired fine. The Australian government actually suppressed the Canadian video because the very public controversy surrounding the army’s reluctance to accept the Owen.

I have seen original trials film still trying to get a copy out of production. Suffice it to say its reliability was astounding even by the highest modern standards.

Inches thick in Tropical mud a quick shake off and back into action. Dirt and water not even a consideration think along the lines of the Legend that AK has built for reliability Owen might just out do it.

I think IAN and everyone else reading this page may be interested in some of this now found archive footag of the Owen gun in promo:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=23M6H_rec6Y

Great find, Cameron! I had seen some of that footage at another site that claimed copyright ownership of it, and I couldn’t repost it.

I have seen video of an Owen gun been dipped into thick mud, then removed and it fired straight away. With no cleaning at all.

This is pretty much my favourite design of all time. Simple, reliable, robust, and with a history so complex and complicated it really needs a book to explain it all (which is where Wayen Wardman’s “The Owen Gun” comes in handy). The Austen is also an interesting gun, especially the Mk II which had an all aluminium receiver, but it can’t hold a candle to the Owen.

Being one of the few that’s actually seen and handled an Owen (but I must confess not actually fired,)I would never seriously take issue with those who have really used them in combat. Were the issue to come up (unlikely in 2013) and based soley on their reputation, I’d gladly accept issue and most likely be happily impressed by their merits.

That being said, way back when, (in the late 1960’s) I found them very heavy for something firing 9mm; Considerably less than sleek, meaning too many projections in all directions to make entrance and egress from either a helicopter or armored vehicle easy; And Lt. Col. John George (“Shots Fired In Anger”)has succinct commentary on the negative aspects of the top-mounted magazine in real combat, to recommend that feature (factory painted feature notwithstanding.)

Anybody got one they want to loan me? 🙂

The F1 eventually replaced it & was killed off by the M16 lighter with a better cartridge

Probably relates more to his lack of soldierly skills than reality the F1 was blisteringly fast to use Magazine changes can be done in the blink of an eye literally. Troops in the Jungle WW2 preferred the Owen precisely for the reason it did not hang up in growth plus its reliability. The top mag only requires a light spring needing no special mag filler bottom eject means “Everything” simply falls out the bottom of the gun.

Hi

my grandad was a true marksmen and he died like that , i followed him for miles around the scrub chasing a crow or some other small animal that was hard to hit but thats the way he rolled , so his story was a bit one sided cause he didnt like semi auto or automatic weapons much . hes in new guinea showing the new blokes the weapons and training them on em and he said a heap of aussies copped a heap in the back from there mates pulling tangled owens through vines and off theyd go , very unpredictable . he was very unpleased with me one trip when i showed up with an sks , i dont think i got anything and used about 300 bullets , i think he shot 4 descent pigs with 4 bullets from his favourate 22250 .

I’m curious to know whether the Owen left you with any blisters on your support arm, I once had a downward ejecting Browning .22 auto that had quite a knack for doing so. 😉

The F1 was also Top Mounted Mag bottom eject never had a problem there was no front grip just a small tab in front of the ejection port, to prevent your hand covering it.

Funny you should mention that: Since I never actually fired an Owen, I can’t comment. But I did work with an M60 that had a propensity for ejecting red-hot cartridge cases down the shirt front of an infamous 20 year old ROTC 2nd LtT Ca 1969 that became an ongoing source of enormous entertainment for we grunts of that era. As long as one’s commentary was prefaced with the word “Sir,” the commentary was beyond reproach. “Perhaps you shouldn’t stand there. SIR.” was always a good one. “SIR, perhaps you should not snuggle quite so close to the actually firing machine-gun in the future… (Please disregard my inadequate attempts to muffle my laughter…”)

(“Please ignore my cohorts who wish to have your demonstrate your ensuing dance to those who did not see it originally… Now tuck your shirt back in…SIR…”)

The Owen had a reputation for reliability that is still spoken of with reverence. Virtually unstoppable regardless of any abuse thrown at it. Canadian test reports described it as – Reliability – “Superior to any other SMG” A must have item for any British or US soldier that could get one in the Pacific. The top mounted Mag makes carrying a breeze. My own experience is with the F1 SMG also top mounted Mag so comfortable to carry it feels un natural after carrying regular weapons.

Obtained new document from Australian War Memorial

Quote “An authoritative assessment of the qualities of the Owen gun is to be found in the report of tests conducted by the Ordnance Board of Britain during December 1943. In competition with five other guns, the Owen was rated first in four of the five tests and first in over-all order of merit”. Apparently the reason for the slow take up of the Owen was the Brits promised a high quality SMG the military here nearly fell over when they saw the piece of junk (STEN or as British troops called it Stench Gun) the Brits were offering. They also stiffed Australia on the quality of tools to make them as well as charging those damn colonials top dollar for the privilege. The manufacturer of the AUSTEN claimed a build time of 6.5 hours compared to 37 for the STEN the Owen was the preferred weapon of front line Australian troops the AUSTEN was kept to the rear.

Copy & paste link to view footage not the original Evelyn Owen Tests they were more rigorous . Some extremely poor weapons drills probably by people roped in for the footage.

http://www.t3licensing.com/video/clip/48050209_2200.do?assetId=clip_8892728&keywords=owen%2Cmachine%2Cgun

Owen Gun Tested Against Other Sub-Machine Guns

Description:

Soldiers test a variety of sub-machine guns while sand is sprayed onto the guns.

I try but can’t imagine the mechanical part of the conversion from semi-automatic to automatic, and how the trigger works for launch .I hope further explanation or video.tnx

my dad carried an owen across the owen stanleys in 44 45,and swore by it. I carried an f1 from 68 to 72 and loved it .it was replaced by that yankee matell toy the armalight. how many yanks were found dead with an armalight dismantled beside them will never be disclosed.

Australian Patent 115,974 was issued to Evelyn Owen for “Improvements Relating to Automatic Weapons” in 1942. It has detailed drawings and descriptions of the Owen Gun, the Trigger Mechanism and the Bolt System. Would be an interesting addition to what is available here.

My dad was an Owen gunner in 2/10 Comando sqn innew guinea Aitape/Wewak. He reckoned it very good for close up combat 5 to 15 yards or so.

I also used Owen and F1. Standard joke was at CO’s orders “disarm the Lts its CO’s orders” the Owen was dangerous.

In battle 9mm does not match 7.62mm or 5.56mm. In Vietnam nigels used to get up and run away after being hit with the Owen and F1.

Both were a pleasure to fire.

Tango

I

I became interested in this Owen smg as a result of my liking for Australian cinema. Just having finished viewing the entire mini series of “The Heroes”, 1&2, I became interested especially in the Owen and Austen, both of which were used in part 2 of the series. Unlike the very good, but technically flawed movie “Attack force Z”, “Heroes” finally showed the true usage of Australian forgotten guns, especially the 2 guns I have mentioned. Just looking out for a deactivated example now, here in England, but dream on, I guess! There are wood/metal mix replicas available, but at less than half the weight of the originals, and a hefty price tag, they’re just very expensive toys!

there is actually a whole book about it

Many years ago (in the 60’s) as an infantry signaller I regularly carried an Owen – or OMC (Owen Machine Carbine)as we called it. The balance of the weapon made it comfortable to carry and sort of compensated for the weight. The only problem we experienced was with the magazine latch. On a worn weapon/magazine you would need to “bump” the top of the magazine with your hand to ensure it clicked into place. If not correctly seated you would have a stoppage due to feed/eject issues. Hitting the top of the magazine soon to became standard practice when reloading. There were several occasions when my mate Tony – who also carried an OMC – smacked the top of the magazine too hard and watched as all the rounds cascaded out of the ejection port and onto the ground.

I have fired both the Owen and the F1, way back when I was in the Australian Army. The Owen long after it had been retired and by chance, the F1 ’cause the ARes used them until the mid-1980s. Of the two, I preferred the Owen. It’s weight made it a steady, easily aimed shot. I was able to hit targets out to 100 metres with single shots. The F1 was interesting and an obvious development of the Owen. It retained the top mounted magazine ’cause that was what Australians were used to, in an SMG. It use the butt, the pistol grip (and trigger group) and cocking handle from a rifle L1a1, which made it cheaper to manufacture. The F1 was light and easy to use but not as accurate as the Owen.

Thank you so much Grant for this fascinating and detailed account of the Owen’s history. I hired one for a short war film I made set in New Guinea 1942 and even made a couple of prop ones out of plumbing copper pipe and a vacuum cleaner part. The original handles of the Owen were made of bakelite!

Regards,

Arnum Endean

DARLINGTON

SYDNEY

I am alive today because my father used the best sub machine of ww2 the owen gun .I would not of been born it saved my fathers live thus mine see i.w.Kelly mm beaufort north borneo june 27 th 1945

I found I.W Kelly, but I could not find the recommendation online. Australia does not have any Gazettes online dated before 2003, but I found the London Gazette he was in, for anyone else interested.

https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1516617/

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/37293/supplement/4886/data.pdf

at 3 min 48 seconds I thought you would have a very sore left thumb 😉

From video;

“Off and hi” – errr, actually,no, Sten gun even has a patent on its sear,trigger and disconnector.

Most sub guns of the era all got semi feature, with exception of mp40.

Probably was too xcited for holding an Owen first time 🙂

My granddad used one in the Vietnam war in 1966 he was in the 5th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) and he used the Owen smg and liked it very very much. I remember him tilling me stories of him using the gun in combat and cleaning the firearm and said, and I quote” the Owen looks like pig ass, the mag sticks out like dog’s balls but she was a ripper of a gun and she would run all day, every time I pulled the trigger she went bang, easy to clean, and the barrel with just a pull of a pin out she pops,no fart arsing about with a screwdriver or tool. if some fella buggered up his barrel and need to replace it, done in under 30 seconds”. Also one of my mates he is currently in the Australian SAS and he said that there are still some sitting in army gun racks all over Oz

I was with a group of diggers tasked with disposing boxes of ww2 9mm ammo so what did we do but fire it off at the range. We put full 10000 bullet boxes though our Owens. No discernible barrel wear or stoppages occurred in the two day blaze away with the biggest problem being gathering up the empties! Became pretty good at hitting cans with 100m hip shots. It was a good reliable field SMG and ultimately replaced by the F1

i was in the ares right through the 80/s just missed out on the owen the older blokes swore by it we had the f1 to about 85 which meant after it went no more browning hi powers either it was actually quite accurate as long as you new that it was zeroed low and left to account for clime on full auto i once watched the stick that held up a f 11 target a 2×1 cut off by repeated single shots . It to would dump the rounds if the mag was smacked too hard which we were taught to do we were taught hip to 25 shoulder rear sight down to 5o sight up 100

cartierbraceletlove Yum! Yes please! I’m so upset I just started eating right. Maybe I can do a weekend cheat? I know what’s for breakfast in the morning! Thanks for sharing.

falso cartier anelli in oro http://www.gioiellibuonmercato.org/

Are there any known mk. 11 Austen msg. in captivity. I had one a long time ago, and would love to know who owns it now.

No. Using the correct grip, ejected cases were well clear. One point: no Owen I’ve seen on YouTube has the safety slide, meaning they somehow got into foreign hands before all issued guns were so modified. The slide was fitted to the rear of the receiver such than when moved to the right it locked the cocking handle either to the rear or in the closed position. Why? Because the safety catch was not reliable, and we were instructed never to set the safety catch in the safe position but to use the slide to lock the bolt open or closed. It was ten times the gun than the F1 was and a million times better than that abomination the M16!

I used and fired the Owen Gun in the CMF (Australian Reserve Army) for a decade from 1965 to 75. The Owen Gun was our smg. It was excellent, highly regarded and really easy to use and maintain. The F1 was a modernised version but was a bit less user friendly to fire. I found it easy to fire accurately from the from the hip.

I was told that the main reason that the smg was dropped from the equipment schedule was that it was found to have insufficient hitting power compared to more modern weapons.

Very cool. I believe this gun is Owen Zastava Pitt’s namesake from the Monster Hunter International series.

sometime back I read (somewhere on line) of an ‘after action report’ filed by a platoon commander of the Aussie army wherein the description of an engagement by his troop assaulted by a large number of Chi-Com troops in the Korean police action. The Chinese used a ‘massed attack’ strategy and the Aussies obliged them with blistering fire from their Owen smg weapons to repulse the attack with many enemy casualties.